Physiotherapists are required by the Standards of Practice for Physiotherapists in Alberta and by Canadian law to obtain informed consent prior to conducting an assessment or providing treatment. The purpose of this Guide is to clarify the expectations for Alberta physiotherapists and to address frequently asked questions related to consent. Physiotherapists are advised to review the Consent Standard of Practice in conjunction with this document.

Consent Guide PDFThe requirement to obtain informed consent for a physiotherapy service is established in Canadian lawa1 and reflected in the Standards of Practice for Physiotherapists in Alberta. “The law has generally considered the requirement of informed consent to be based on the fundamental right to autonomy and protection of the person’s integrity. In practical terms, the boundaries of the practice of informed consent have evolved through civil liability jurisprudence, and in Canada have not significantly changed since 1980.”2 Indeed, informed consent expectations are so well established in the Canadian context that some legal scholars refer to these expectations as “the Doctrine of Consent”.3

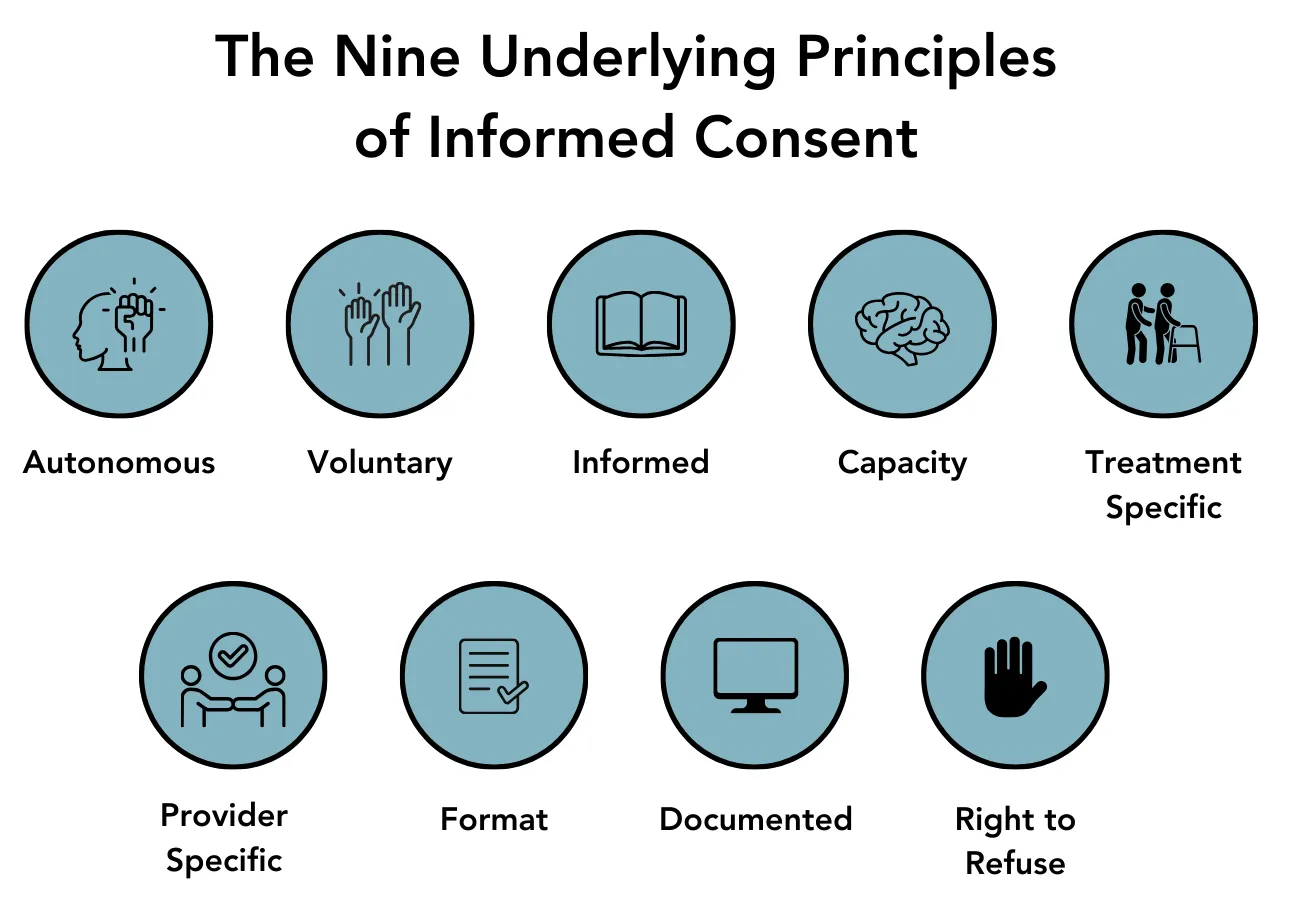

Informed consent is a process by which a physiotherapist seeks and receives a client’s permission to proceed with an agreed course of physiotherapy service.4 According to the Standards of Practice, physiotherapists are required to obtain “clients’ ongoing informed consent for the delivery of physiotherapy services.”5

“Clients can expect that they will be informed of the options, risks, and benefits of proposed physiotherapy services, asked to provide their consent, and that the physiotherapist will respect their right to question, refuse options, and/or withdraw from services at any time.”5

Consent is a cornerstone of all therapeutic interactions. Consent, in turn, rests on a foundation of clear, effective, client-centred communication.

The College of Physiotherapists of Alberta regularly receives questions about different aspects of consent, including questions about how to navigate challenging situations related to consent and consent processes in physiotherapy practice. The purpose of this guide is to elaborate upon the performance expectations established in the Consent Standard of Practice and to address common questions.

a. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 7; Reibl v Hughes 1980 SCC 23; Hopp v Lepp 1980 SCC 14; Fleming V Reid 1991 ON CA 2728; Malette v Shulman 1987 ON HCJ 4096

Informed Consent Fundamentals

- Physiotherapists cannot obtain consent without first engaging in a process of informing the client about the proposed assessment or treatment’s purpose, expected benefits, and related risks. Consent is not consent if it is not informed.

- Informed consent must be received before the physiotherapist commences the assessment or treatment. Consent after the fact is not consent.

- Consent is physiotherapy service and provider-specific.

- Consent can be rescinded at any time and for any reason. Physiotherapists must ensure that they have the client’s ongoing agreement to proceed with a physiotherapy service.

- Express informed consent is strongly advised. When professional conduct matters arise that relate to issues of consent, they often pertain to disagreements about whether informed consent was obtained by the physiotherapist. Obtaining express informed consent following a robust informed consent discussion helps to avoid this issue.

Consent is a cornerstone of all therapeutic interactions. Consent, in turn, rests on a foundation of clear, effective, client-centred communication.

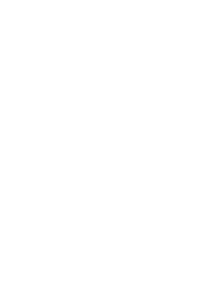

1. Autonomous

The ethical principle of autonomy or self-determination underpins the obligation to obtain informed consent. Physiotherapists are ethically and legally bound to communicate with patients so they can make informed choices regarding their own care.

2. Voluntary

Consent is invalid if obtained by coercion, undue influence, or intentional misrepresentation. Consent should be given in an environment free of fear or compulsion from others, including family members and health-care providers.

3. Informed

Consent is invalid if it is based on incomplete or inaccurate information. Consent must be based on a careful discussion of all relevant information and considerations regarding the intervention. Different strategies should be used to ensure patient understanding including: verbal explanations, handouts, visual aids, consent forms, asking a patient whether they understand the information presented, and having them explain it back to check for understanding.

4. Capacity

Consent is only valid when the person providing consent has the capacity to do so. The patient must have the ability to appreciate the nature and consequences of the consent decision.

5. Treatment Specific

As already described, the patient provides consent to a specific treatment, after being informed of the risks and benefits of the treatment proposed. A patient can consent to receive treatment and still decline certain aspects or components of the proposed treatment.

6. Provider Specific

Informed consent is personal and normally authorizes a specific person to carry out a specific intervention. Patients have the right to intervention by a health professional with whom they have a relationship and the right to consent to or decline a physiotherapist’s assignment of intervention responsibilities to another individual. The physiotherapist providing the intervention is responsible to obtain the consent.

7. Format

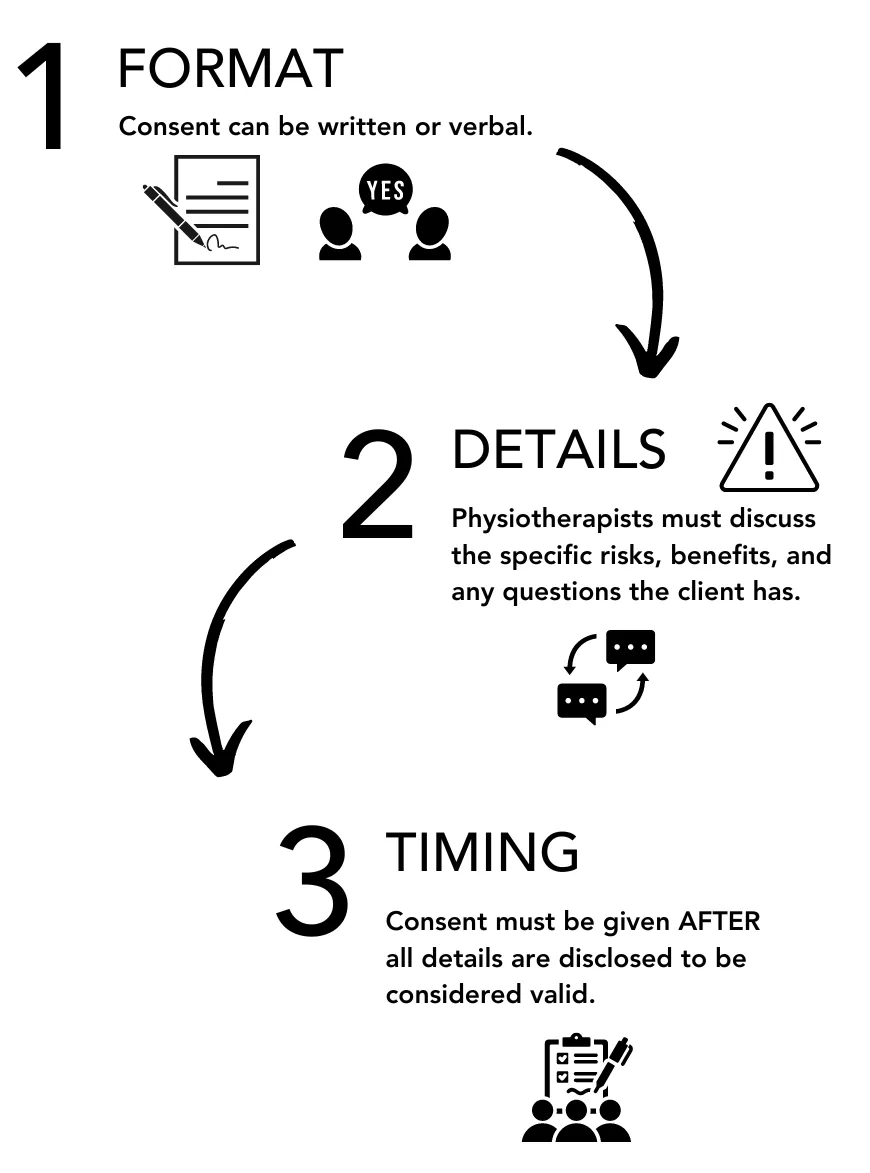

Informed consent can be written or verbal. While the law does not generally require a “written consent”, a consent form signed by the patient provides evidence that consent has been obtained.2

If an intervention is invasive, carries an appreciable risk, or is likely to be painful, it is prudent for the physiotherapist to obtain written consent.2

Verbal consent must be documented in the treatment record by the physiotherapist.3

8. Documented

Whether the physiotherapist accepts verbal consent or has the patient sign a consent form, the physiotherapist is advised to document the consent process including the information provided to the patient, and when/how consent was obtained. A signed consent form provides evidence that consent was obtained but does not necessarily indicate that the consent was informed and cannot replace a detailed informed consent discussion.2

9. Right to Refuse

Patients have the right to refuse intervention, regardless of the consequences or how beneficial or necessary a treatment may be. Patients also have the right to change their mind and withdraw previous consent at any time during care.3

Just as consent must be informed, it is important that a patient’s refusal of consent/treatment be informed. “When patients decide against recommended treatment…, discussions about their decision must be conducted with some sensitivity. While recognizing an individual’s right to refuse…, [physiotherapists] must at the same time explain the consequences of the refusal without creating a perception of coercion in seeking consent. Refusal of the recommended treatment does not necessarily constitute refusal for all treatments. Reasonable alternatives should be explained and offered to the patient.”2

Physiotherapists are advised to document a patient’s refusal, the information provided to the patient regarding risks or consequences of refusal, and the patient’s rationale for refusing, if one is provided.

The informed consent process relies on the essential competency of clear, effective, and client-centred communication. Robust informed consent conversations

are enabled by communicating with clients in plain, easy-to-understand language.8 The use of technical terms or jargon is not recommended and is contrary to the purpose of gaining informed consent.

The informed consent process begins the moment the client arrives to receive physiotherapy services for the first time. As the physiotherapist introduces themselves and conducts the client interview, they are actively working to build a therapeutic relationship with the client and to begin to understand the client’s perspective, concerns, values, and goals.

When a physiotherapist begins to understand what matters to the individual client in front of them and that individual’s priorities, lived experiences, and health conditions, the physiotherapist can begin to develop a treatment plan that is client-centred. Furthermore, they can engage in meaningful discussions about the intended benefits and risks of the proposed physiotherapy services.

Clients cannot provide valid consent if they do not fully understand what they are consenting to and the implications of that consent. It is essential that the client understand the nature and purpose of the physiotherapy services proposed. The consent process must include an explanation of the physiotherapy diagnosis and recommended treatment including benefits, risks, and other options for treatment.

Supreme Court of Canada decisions have established that health professionals must “pre-disclose what a reasonable person in the plaintiff’s [client’s] position would consider relevant to their health care decision making” including both the health professional’s knowledge of the risks and what a reasonable person in the client’s position would consider relevant. 9,10 Physiotherapists use a range of communication strategies and techniques to support this process including:

- Active listening, paraphrasing, and checking in to clarify understanding.

- Attention to non-verbal communication.

- Appropriate use of open- and closed-ended questions.

- Adjusting communication style as needed.8

A detailed discussion of client-centred communication is beyond the scope of this guide. Physiotherapists are directed to the Patient-Centred Communication e-Learning Module8 for a detailed discussion of client-centred communication strategies and techniques.

Supreme Court of Canada decisions have also affirmed that the duty to disclose also includes a duty to ensure that the client understands the information provided.9 An Ontario court case (Lue v St. Michael's Hospital. 1997 OTC 21) established objective criteria by which the degree of client understanding can be determined. Physiotherapists may wish to employ these criteria when considering their consent processes and whether they have obtained informed consent by considering whether:

- the client asked pertinent questions;

- sufficient time was spent providing the information;

- visual aids were used if relevant;

- information was put in writing; and

- the client utilized family assistance in understanding the information.9

Remember that the purpose of this client-centred communication, meaningful risk disclosure, and opportunity to ask questions is to provide the necessary information to enable the client to make informed decisions about accepting or refusing the proposed physiotherapy service.

Discussing Risks

When discussing the risks related to a specific assessment or treatment technique, the physiotherapist must disclose and discuss both the material and special risks related to the physiotherapy service.

Material Risks include risks that occur frequently as well as those that are rare but very serious, such as death or permanent disability.4

Special Risks are those that are particularly relevant to the specific client when typically, these may not be seen as material. Consent discussions and requirements extend to what the physiotherapists know or ought reasonably to know their client would deem relevant to deciding whether or not to undergo treatment.4

An example of a material risk in physiotherapy practice is the risk that an upper cervical spine manipulation could lead to vertebral artery dissection. When discussing this risk in practice, physiotherapists must:

- Be honest about the risk.

- Provide accurate information quantifying the risk for the client.

- Be transparent about the potential consequences of this type of patient safety incident for the client and the client’s long-term health.

- Discuss the physiotherapist’s rationale for performing the manipulation in light of the risks.

- Disclose the physiotherapist’s own authorization and experience in performing the cervical spine manipulation.

- Describe the actions taken by the physiotherapist to mitigate the risk of harm.

This is not the only material risk that is recognized within physiotherapy practice; however, it is used for illustrative purposes for how physiotherapists discuss material risks. Given that the risk of a vertebral artery dissection is one of the more severe potential patient safety incidents arising directly from a physiotherapist’s services, most clients would view this potential outcome as a material risk.

Special risks can range in nature and severity. Sometimes a client will view an anticipated but undesirable outcome as

a risk based on their perspective and values. For example, muscle soreness following dry needling could be considered a material risk due to the frequency with which that typically minor outcome occurs. However, muscle soreness could constitute a special risk in the case of a competitive athlete if it affects their performance at an important competition.

How a client views a risk can depend upon:

- The chance of the outcome occurring.

- The anticipated benefits of the treatment.

- How much harm may arise from the event?

» Life-threatening outcome.

» Short-term (temporary) or long-term (permanent).

- How in control of the decision the client feels.

- How much the client feels they can trust the physiotherapist.

- Whether the client feels they understand the situation.11

When having risk discussions, it is important that the physiotherapist tailor the discussion to the type of potential harm, the probability of harm occurring, and what they know about the client and the client’s values.

Understanding risk can be challenging. How risks are communicated is important. For example, if a treatment doubles a person’s risk of a specific outcome, it is important to not only know that the risk is doubled, but how frequently the risk occurs. If a risk goes from being a 1 in 10,000 risk to being a 1 in 5,000 risk that would still generally be considered a rare risk. This would be viewed very differently from a risk that has gone from a 1 in 10 to a 1 in 5 rate of occurrence even though in both examples the risk has doubled. Simply saying a risk has doubled can be misleading.11

Questions

Clients must be given the opportunity to ask questions and gain further clarification.1 Beyond asking if the client has questions, the physiotherapist should take steps to make it clear that questions are welcomed and to normalize that clients will have questions. The physiotherapist can do so through the words they use when soliciting client questions. Instead of saying “Do you have questions?”, or “Any questions?” Consider asking “What questions do you have?”

Physiotherapists must recognize that clients “may not know enough to enable them to frame specific or even general questions.”12 Depending on the situation, physiotherapists may need to volunteer information by saying “Other clients in a similar position have asked me this about this treatment. Would you like some more information about that?”

Both clients and providers must understand that clients have the right to change their minds and withdraw consent at any time.5

The recognition that consent can be withdrawn at any time informs the College’s rationale for the performance expectation that the physiotherapist ‘obtains the client’s ongoing informed consent to proposed physiotherapy services.’5

When providing care, physiotherapists ought to always know that they have the client’s permission to proceed with an agreed course of physiotherapy service. If that permission is ever in question, the physiotherapist must pause and reaffirm that consent is in place.

Physiotherapists must closely monitor their client’s responses to physiotherapy services. This is not only necessary to gauge the effectiveness of treatment, but also to ensure they have the client’s consent to continue. Physiotherapists must recognize that many physiotherapy services, such as those which include touch and close proximity to the client, have the potential to evoke a trauma response from a client.

Trauma-informed practice means that physiotherapists must always consider the potential that a client may have experienced trauma in their lives and that a physiotherapy assessment or treatment could elicit a trauma response.13 Physiotherapists should monitor their client’s responses for reactions including but not limited to:

- Physically withdrawing.

- Altered breathing patterns.

- Diminished responses to questions.

- Appearing to disengage from the interaction or ‘zone out’.13

A detailed discussion of trauma-informed practice and different types of trauma responses is beyond the scope of this guide. However, when a physiotherapist notes a change in the client’s responses or has other reasons to be concerned about the client’s ongoing consent to services, they are advised to pause the service and clarify if the client continues to consent. This can take the form of stating what you are observing, checking in on and validating the client’s experience, and directly asking the client if you have permission to continue.13 For example, “I noticed you got quiet just now. How are you doing? Would you like me to stop for today, or pause and give you a couple of minutes?”

Clients have the right to change their minds and withdraw consent at any time.

Physiotherapists ought to always know that they have the client's permission to proceed. If that permission is ever in question, pause and reaffirm that consent is in place.

A client’s attendance at a physiotherapy appointment or failure to say “no” does not necessarily mean that informed consent is in place. The simple act of attending a physiotherapy appointment does not ensure that the physiotherapist has provided the client with the necessary information to make informed decisions about the services they receive and that informed consent has been obtained. Attendance at a physiotherapy appointment cannot be considered “informed consent” in and of itself.

Attendance at a physiotherapy appointment or failure to say "no" does not mean that informed consent is in place

Furthermore, due to the power dynamics in place between clients and physiotherapists, and the influence that third-party payers can have on insurance claims, clients may feel coerced to attend physiotherapy appointments, that they do not have meaningful choice in the physiotherapy services that they receive, that they cannot speak up or ask for a different approach, or fear that asking questions or requesting modifications to a treatment plan could jeopardize an insurance claim.

Relying on implied consent can lead to challenging situations where a client and their physiotherapist disagree as to whether informed consent was in place after the fact. This can happen in situations where patient safety incidents arise in the course of providing physiotherapy services, and after the incident, the client reports that they did not provide informed consent to the physiotherapy service. It is, therefore, preferable to obtain express informed consent.1

As the risk of an assessment or treatment increases, the need to obtain express informed consent also increases.3

Reaffirming Ongoing Consent

Although consent must be informed and ongoing, that does not mean that each time a client receives physiotherapy services the physiotherapist must engage in an extensive discussion of the client’s perspectives and values, the anticipated benefits, and material and special risks of the physiotherapy services.

The College’s expectation is that each time a client receives physiotherapy services, the physiotherapist confirms that they have the client’s agreement to proceed with the services planned. Confirming the client’s ongoing agreement with the plan and creating a space for the client to decline or to ask questions about the treatment helps to avoid misunderstandings and disagreements after the fact and helps to protect the client’s autonomy.

Implied Consent and Plans of Care

Within physiotherapy practice, there can be situations where a physiotherapist is working with a client who does not have the capacity to provide their own consent for physiotherapy services. Examples include physiotherapists working with minors and physiotherapists working with adults who have been deemed to lack capacity. In these situations, the physiotherapist is required to obtain consent for the client’s care from the appropriate individual.5 There are times when the ability to obtain informed consent from the appropriate individual can be challenging due to access to the client’s guardian or agent.

In such cases, a physiotherapist may wish to obtain consent from the client’s guardian or agent for a “plan of care” expected to continue over a series of treatment visits. In this case, the client’s attendance and participation in the agreed plan of care may be considered implied consent. Provided there is no significant change in the nature, expected benefits, or risks of treatment, a physiotherapist may presume that consent to physiotherapy services continues.

However, the physiotherapist is expected to clearly articulate a detailed plan of care, obtain consent from the client’s guardian or agent, and provide updates and reporting to the client’s guardian or agent at agreed intervals or if the plan of care changes from what was agreed upon to support ongoing consent.

A new informed consent must be obtained whenever there is a significant change in the client’s capacity, condition, treatment plan, expected outcomes, or risks.

The next section of this guide provides a detailed discussion of capacity considerations for physiotherapists.

Health care providers often use the terms "capacity" and "competence" interchangeably.14 In Alberta, the term capacity is the word used, and is defined in the Adult Guardianship and Trustee Act as “the ability to understand information relevant to a decision and to appreciate the reasonably foreseeable consequence of making a decision or the failure to make a decision.”15

One of the guiding principles of the Adult Guardianship and Trustee Act of Alberta is that an adult (anyone over age 18) is presumed to have the capacity to make health care and other decisions unless determined otherwise through a capacity assessment.16

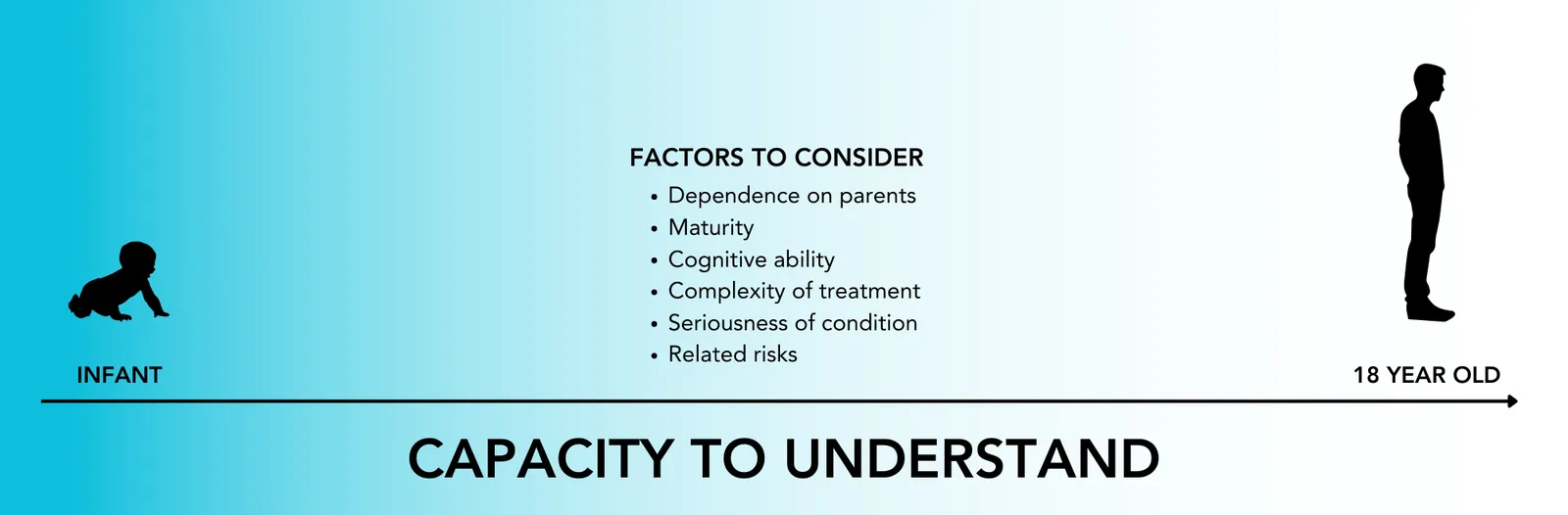

Capacity comes in “degrees” with one’s capacity to make decisions being impacted by the nature of the decision and risks related to the decision.14,17 An individual may have the capacity to make some decisions and not others. For example, they may have difficulty making complex health decisions but be capable of making decisions about finances and social activities.16

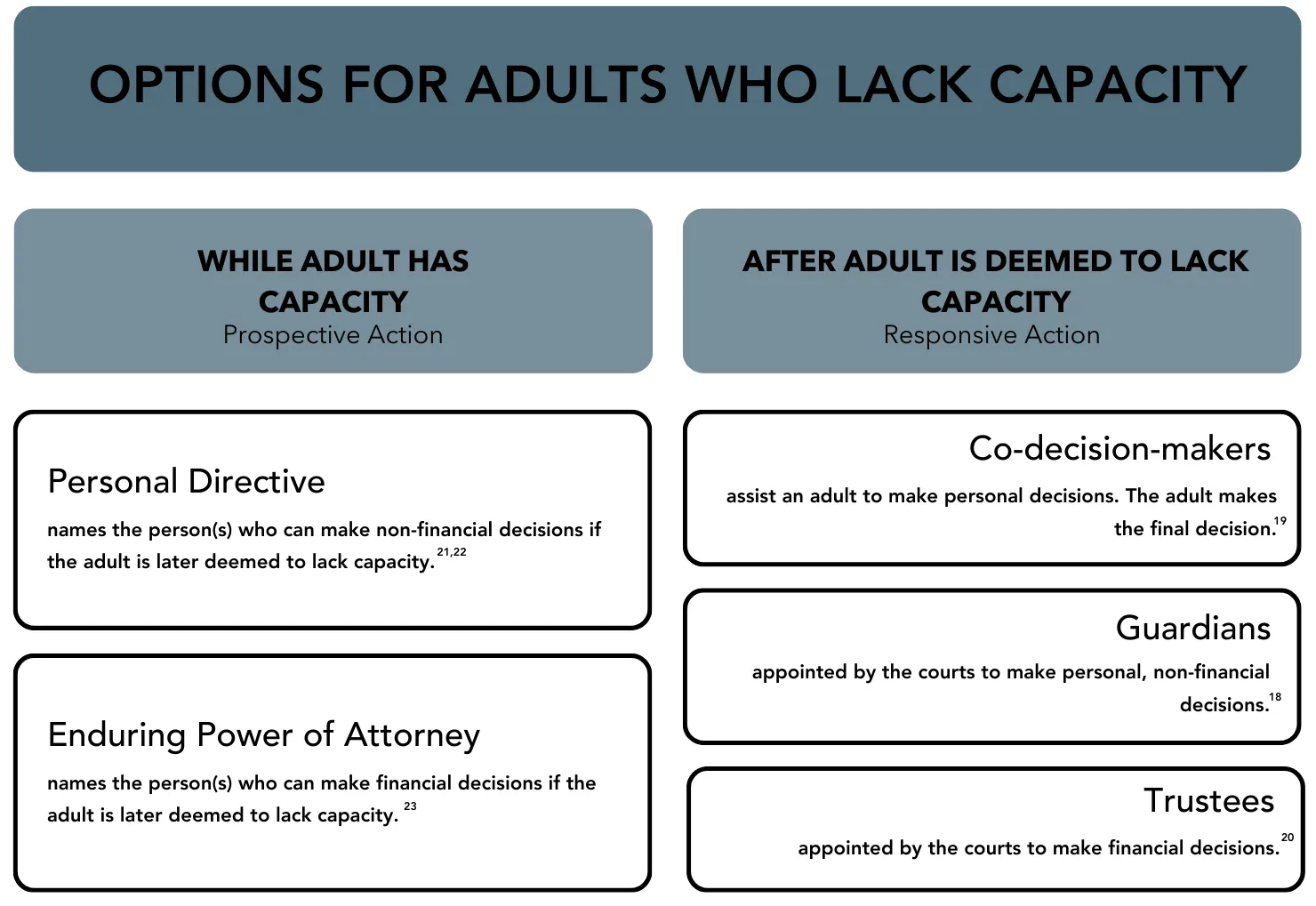

In this section we will discuss:

- Legal instruments in place to enable decision-making on the client’s behalf.

- Identifying the appropriate individual to provide consent on behalf of the client if they cannot provide consent for themselves.

- Managing adult clients who appear to lack capacity.

- Capacity concerns in urgent or emergent care situations.

Questioning Capacity

As part of informed consent processes, all health professionals routinely gauge whether a client can understand information and appreciate the consequences of health decisions.

If a physiotherapist is questioning a client’s capacity, the key question is “the capacity to do what?” A client may lack the capacity to consent to some components of a health care service but not others due to the nature and risks of the service in question and their ability to understand the information related to the decision.16 A physiotherapist should, therefore, consider the nature of the physiotherapy service for which the consent is being sought when questioning whether the client has the capacity to provide consent.

Importantly, the fact that a physiotherapist disagrees with a client’s decision does not make the client incapable of making their own decisions.16,17 As is sometimes noted, concerns about capacity often disappear if the client is making decisions consistent with the physiotherapist’s recommendations.

In Alberta, before an adult is legally deemed to lack capacity, they must undergo a capacity assessment. Physiotherapists do not engage in formal capacity assessments to provide courts with information to help determine whether a co-decision-maker, guardian, or trustee should be appointed.15,18 A capacity assessment is only completed if there are legitimate reasons to do so. A physician must complete a medical examination to ensure that the person’s decision-making abilities are not being affected by a condition that is temporary or reversible.16

Assuming the adult’s decision-making is not being affected by a temporary or reversible condition, a capacity assessment can be completed by a qualified capacity assessor to determine:

- If a personal directive should be enacted.

- If one of the following decision-makers should be appointed:

» Co-decision-maker.

» Guardian.

» Trustee.6

According to the Consent Standard of Practice, physiotherapists are required to obtain “informed consent from the appropriate individual, according to applicable legislation and regulatory requirements, in cases when clients are incompetent, incapacitated, and/or unable to provide consent.”5 If an adult is found to lack capacity, a range of options are available to assist with decision-making on their behalf depending on the findings of the capacity assessment and the areas of decision-making where the adult needs support.

Co-decision-makers assist an adult who needs help making personal decisions on their own. The co-decision-maker and adult work through decisions and the adult makes the final decision.19

Guardians are appointed by the courts and make personal, non-financial decisions about such things as health care, where to live, participation in social activities, and legal proceedings.18

Trustees are appointed by the courts to make financial decisions.20

Personal Directives are legal documents made by the adult when they have capacity, that allow the adult to name the person or persons who are able to make decisions on their behalf if they are deemed to lack capacity. The person named in a personal directive is able to make decisions about health care, where to live, and choices about personal activities.21,22

A personal directive may be enacted in one of two ways:

- A specific person is designated in the personal directive to determine the client’s capacity.

- Two health care providers make written declarations that the client lacks capacity.21

Enduring Power of Attorney is a legal document written by an adult when they have the capacity that gives another person the authority to make financial decisions on their behalf if they lose the capacity to make their own decisions.23

Treating a Client Who Lacks Capacity

When treating a client who lacks capacity, the physiotherapist needs to understand which individual has the authority to act on the client’s behalf. In accordance with legislation and the Standards of Practice, if a client lacks the capacity to give informed consent, informed consent must be obtained from an individual with legal authority to provide it.

If a physiotherapist has concerns about a client’s capacity to provide informed consent for a physiotherapy service, the physiotherapist should enquire if an agent has been designated via an enacted personal directive, or if a co-decision-maker or guardian is in place.

Co-decision-makers and guardians are appointed by the court. The individual acting as the client’s agent should have a copy of the court order. Individuals identified as agents through

a personal directive should be aware of that fact and the personal directive would be enacted as previously described.

Clients Without Agents, Co-Decision-Makers, or Guardians

Physiotherapists sometimes encounter situations where they need to provide services to an adult client who appears to lack capacity. This can occur in the context of providing care in hospital settings and community settings.

In the context of a community physiotherapy practice, if no legal arrangement is in place, the physiotherapist’s duty of care extends to:

- Raising their concerns with others within the client’s circle of care.

- Discussing the situation with the client’s physician or another primary care provider.

- Advocating for a formal capacity assessment if appropriate.

While awaiting formal assessment, the physiotherapist may proceed with treatment that is in the client’s best interests with the client’s family’s approval and the client’s assent.1 However, the physiotherapist must realize that this has the potential to create a challenging situation, particularly if different family members cannot agree on the treatment plan. In cases where the proposed treatment is risky or there is disagreement among family members, the College of Physiotherapists of Alberta recommends that members take a cautious approach to any treatment provided, consider the need to discontinue treatment until questions of capacity and guardianship are addressed, or seek legal advice before proceeding if treatment cannot safely be discontinued.1

In the context of hospitalization, if a client is incapacitated due to acute illness, it is not legitimate to conduct a capacity assessment while the person’s decision-making abilities are affected by a condition that is temporary or reversible.16

In such instances, if the client does not have an agent who has been designated by a personal directive, the provisions of the Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act15 may apply. Section 87 of the Act states that

87(1) Where a health care provider has reason to believe that an adult may lack the capacity to make a decision respecting the adult’s health care or the adult’s temporary admission to a residential facility, the health care provider may assess, in accordance with the regulations, the adult’s capacity to make the decision.

87(2) Subject to section 88, a health care provider may, in accordance with this Division, select a specific decision maker to make a decision for an adult respecting

(a) the adult’s health care

There are specific parameters that apply to this provision of the Act, including which health professionals can select the specific decision-maker. To provide physiotherapy services, what is important to know is that:

- In the absence of a court order, a health care provider can select a specific decision-maker to make decisions about an incapacitated client’s care.

- Physiotherapists are not authorized by the legislation to identify the specific decision-maker.

Discussion of the considerations for selecting a specific decision-maker is beyond the scope of this guide. This selection is subject to the provisions of section 89 of the Act.15

Capacity and Urgent or Emergent Care

In an extreme situation where the designated agent or guardian cannot be contacted for consent, Section 101 of the Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act includes provisions that enable the delivery of emergency care that is necessary to preserve the client’s life, prevent serious physical or mental harm to the client, or alleviate severe pain without client consent, provided that the client lacks capacity.15 These provisions specifically name physicians as the care provider in question and the Canadian Medical Protective Association cautions that:

there must be demonstrable severe suffering or an imminent threat to the life or health of the patient. It cannot be a question of preference or convenience for the health care provider; there must be undoubted necessity to proceed at the time. Further, under medical emergency situations, treatments should be limited to those necessary to prevent prolonged suffering or to deal with imminent threats to life, limb or health.24

In such cases, provided a physiotherapist is working as a member of an interprofessional team to deliver physiotherapy services necessary to prevent prolonged suffering and deal with imminent threats to life, limb or health, the College’s view is that such action is consistent with the ethical principle of beneficence and the expectation stated in the Consent Standard of Practice that the physiotherapist:

acts in accordance with ethical principles of beneficence and least harm in instances where consent cannot be obtained from the appropriate individual for provision of services to a client who is incompetent, incapacitated and/or unable to provide consent.5

Consent, Capacity, and Impairment

Cannabis and alcohol are two examples of substances that may impact a client’s capacity to provide consent. The issue is not what substance is in use, but rather whether the substance impairs the client’s capacity to provide informed consent. Physiotherapists should employ consistent policies and processes when faced with a client who is impaired by any substance.25

Some treatments come with more risk than others. If a physiotherapist has concerns that the client does not appreciate the nature and consequences of the informed consent decision, regardless of the reason, the physiotherapist should neither seek nor accept consent for that physiotherapy service. This may impact the treatment plan and the approach the physiotherapist will take.

Again, the physiotherapist should ask themselves, “capacity to consent to what?” Depending on the specific situation, it is possible that the client may have sufficient capacity to consent to lower-risk treatment options. The physiotherapist will need to use their professional judgment when making this determination.

** In this section, the term minor is used to refer to any patient under the age of 18. The term child is used to refer to a patient whose age is less than 14 with the exception of direct quotations or sample questions to employ in practice. The term patient is used to refer to the individual receiving treatment in alignment with the definition of client as being inclusive of both the individual receiving treatment and their guardian(s).

It is generally assumed that an individual who is under age 18 is not able to provide consent, and that consent must be obtained from the minor patient’s legal guardian. However, legal scholars have argued that “Canadian cases have held that there is no age below which minors are automatically incapable of consenting to medical procedures and that it is a minor’s right to consent if he is [they are] able to fully understand what is involved with the procedure in question.”7

As with adults, the key question is whether the minor has the capacity to provide informed consent. Specifically, the capacity to understand information relevant to the decision, and the foreseeable consequence of making or failing to make a decision.

What does this mean for the physiotherapist’s responsibilities?

When providing physiotherapy services to children, it is appropriate for the physiotherapist to obtain consent from the patient’s legal guardian and assent from the child.

When providing services to adolescents, particularly older adolescents, the physiotherapist will need to carefully consider whether the minor has the capacity to provide valid informed consent. It is appropriate to obtain consent from the adolescent’s legal guardian, but it may also be acceptable to obtain consent from the adolescent. In a best-case scenario, both the legal guardian and the patient will agree with the plan of care and provide consent.

In instances where the legal guardian is not present, or where the patient and their legal guardian do not agree, the physiotherapist will need to carefully consider the adolescent’s capacity to provide valid consent.

In all cases, the participation of children and adolescents in the decision-making process is important and physiotherapists are advised to consider and respect the evolving decision-making skills and capacity of this population, gaining the minor’s assent to treatment, and giving serious consideration to strong indications of dissent.26

Guardianship and Minors

Matters pertaining to the guardianship of minors can be complex. It is essential that the physiotherapist identify the individual or individuals with the authority to provide informed consent for the patient’s physiotherapy services.

Physiotherapists need to be aware that:

- According to the Family Law Act, both birth parents have equal responsibilities and powers as guardians unless a court order states otherwise. In this scenario, both birth parents can provide consent.27

- Other individuals (same-sex parents, adoptive parents, foster parents, extended family members) can also be a minor’s legal guardian. Any individual with a court order granting them guardianship of the minor can provide informed consent for the minor’s physiotherapy services.

Guardianship and consent considerations when a minor’s parents are divorced:

- If one parent has sole custody of the minor (i.e., the custodial parent), they become the sole guardian of the minor and are the only parent responsible for providing consent for physiotherapy services.

- If a custodial parent consents to treatment for a minor which appears to be in the best interests of the minor, the non-custodial parent cannot stop the treatment by advising that they do not consent to the treatment.”28 The non-custodial parent retains the right to make inquiries and to be given information about the health, education, and welfare of the minor. This does not mean that the custodial parent’s decisions are subject to the consultation and approval of the non-custodial parent.28,29

- If the parents share custody, they also share guardianship, therefore, both have the right to consent to treatment. Cases of shared custody can create challenging situations for the treating physiotherapist if the guardians do not agree about treatment decisions. In such a situation, the physiotherapist will need to work with the guardians to build consensus about a plan of care.28

- Legal guardians are required to act in the best interest of the minor at all times. One parent does not have the “authority to prevent or override the other parent’s consent for treatment that is in the best interests of the child.”28

Common myths and misunderstandings about guardianship to be aware of:

- Stepparents are not guardians of a minor unless they have legally adopted the minor (i.e. the court has issued an order for the adoption)

- A live-in partner of the minor’s legal guardian is not a guardian of the minor unless they have legally adopted the minor or have a court order granting guardianship.27-29

If a minor attends physiotherapy services accompanied by an adult, the physiotherapist is advised to inquire if the adult is the minor’s lawful guardian and is able to provide consent for physiotherapy services.

It is reasonable to assume that a minor’s birth parent is their lawful guardian and can consent to intervention.

If a physiotherapist becomes aware of circumstances that would suggest that an adult accompanying the minor does not, or may not have guardianship of the minor, the physiotherapist is required to ask further questions before providing non-emergency care.28,29

Physiotherapists are advised to ask:

- Are you this child’s legal guardian?

- Are you aware of anything that prevents you from having the authority to provide consent for this child?

- Are there any other guardians who need to be consulted regarding decisions for this child? 28,29

If the physiotherapist remains unsure as to who has the right to give consent on behalf of the minor, they can ask about and document the terms of any custody orders or guardianship orders as described by the parent who brought the minor for treatment. You may also request a copy of the court orders granting guardianship or declaring parental rights upon divorce, if applicable. 28,29

Mature Minor Considerations

As already stated, in some situations, an individual who is under 18 may be deemed a mature minor. A mature minor may give consent on their own behalf, provided they understand the nature and purpose of the proposed intervention and the consequences of receiving or refusing it.27-29

It is the physiotherapist’s responsibility to assess and make the determination of whether a patient under 18 is a mature minor and able to provide valid informed consent. There is no clear test to determine if a minor is in fact “mature.” Physiotherapists should be careful to engage in a holistic assessment of the minor patient to determine if they are a mature minor.

Some factors that may be considered in assessing whether

a minor can appreciate the nature and purpose of the intervention and the consequence of giving or refusing consent include:

- The age of the minor. Although there is no set age for a mature minor in Alberta, sixteen years of age is generally considered the threshold for recognition of maturity by the courts. No Alberta court has recognized an individual under the age of fourteen as a mature minor.

- The maturity and cognitive capacity of the minor and their ability to understand the information provided by the physiotherapist.

- The nature and extent of the minor’s dependence on the parent(s). This relates to the ability of the minor to make an independent decision without coercion and influence of the parent or guardian.

- The seriousness of the condition, the complexity of the treatment, and the risks related to the treatment proposed.29,30

*This is not an exhaustive list.

Physiotherapists should document and be able to explain how they determined that the minor was “mature” and able to make their own health care decisions. They should also reflect on whether a group of their peers would view the decision as reasonable. Importantly, the choice to accept consent from a minor must arise from the assessment of the minor’s capacity to give valid informed consent and not due to what is convenient or efficient for the physiotherapist.

If the physiotherapist has any doubts, they are advised to consider having a second health care provider offer an opinion. Physiotherapists should also follow any employer-directed processes related to forming this determination.

Physiotherapists must also be aware that if a patient is deemed a mature minor, their guardian has “no authority to override or veto the mature minor’s decisions.”28 Again, the determination that a minor is mature is based on their capacity to make informed decisions and is independent of whether or not the physiotherapist agrees with the decisions the minor is making regarding their health.

Urgent or Emergent Care and Minors

As already stated, in an emergency, health care providers can act in the patient’s best interest to provide the care necessary to prevent prolonged suffering or address imminent threats to life, limb, or health.1,28,29

This can arise in some rare situations in physiotherapy practice including acute care service delivery and in the context of sporting-related injuries.

Physiotherapists are advised that a guardian can appoint a person to act on behalf of the guardian in an emergency situation.27 For example, if a minor was travelling with a sports team.

The best-case scenario would be to contact the patient’s legal guardian by phone and obtain verbal consent for physiotherapy services. In doing so, the physiotherapist should have the person at the other end of the line verbally confirm their relationship with the client and their authority to provide consent on the client’s behalf.

It is critical that physiotherapists accurately and completely document informed consent. The Consent Standard of Practice specifies the performance expectation that the physiotherapist “documents that consent was obtained and relevant details of the consent process reasonable for the clinical situation.”5

Format of Consent

As previously stated, informed consent can be written or verbal. While the law does not generally require “written consent”, a consent form signed by the client provides evidence that consent has been obtained.1

However, if an intervention is invasive, carries significant material risk, or is likely to be painful, physiotherapists are advised to obtain written consent.1

If a physiotherapist chooses to accept verbal consent for physiotherapy services, they must document in the treatment record that verbal consent was received.5

Physiotherapists must document that consent was obtained

and the relevant details of the consent process.

"Consent" that is not informed is not consent.

Details Required

Whether the physiotherapist accepts verbal consent or has the client sign a consent form, the physiotherapist is advised to document the consent process including the information provided to the client and when/how consent was obtained. In accordance with the Consent Standard of Practice, a simple check box at the time of the initial assessment (indicating that consent was received) is not sufficient to fulfill the performance expectation as such consent documentation does not provide sufficient detail regarding the anticipated benefits, risks disclosed, and client questions discussed.

Neither a check box nor a signed consent form signifies that a detailed informed consent discussion occurred.1,5

Timing of Obtaining Consent

A consent form signed before the client has received information about the assessment, their physiotherapy diagnosis, the proposed treatment, and the risks/benefits and consequences of receiving or not receiving treatment, for example by completing an intake form, is not informed consent. It has been obtained before the client has been provided with any of the information they need to make an informed decision about their own care.

“Consent” that is not informed is not consent.

Wise Practices

The best-case scenario is to obtain written informed consent from the client, after having the informed consent discussion with them. The physiotherapist would then document the nature and content of that discussion as part of the treatment record.

Q: I am seeing a client who has limited English proficiency. Do I need to arrange for a trained interpreter to obtain informed consent?

A: Interpreters, including sign language interpreters, should be used if any doubt exists about a client’s capacity to understand the implications and nuances of the consent discussion and to provide valid informed consent due to a communication barrier.

It is a best practice to use professional interpreters when obtaining consent from individuals with limited English proficiency. Using a family member, friend, or other health care provider creates a risk that the information will not be conveyed accurately and/or that the family member or friend will convey incomplete information or add their own perspective on the conversation. The resulting consent will not be valid in this case.

When employing an interpreter, the health professional should clearly indicate that an interpreter was used to obtain informed consent. It is also a best practice to have the interpreter sign

a declaration stating “I, (interpreter name), interpreted the information faithfully and accurately.”

The interpreter’s role is to accurately convey all parts of a message without changing the content, meaning, or tone.31

Depending on the population served by the physiotherapy practice, it may also be reasonable to have forms and client education materials translated into different languages. However, the success of that strategy relies on the client’s ability to read their first language.

Q: My client is making a decision that is dangerous and puts their own safety at risk. What can I do?

A: Physiotherapists respect the autonomy of clients to question, decline options, refuse, rescind consent, and/or withdraw from physiotherapy services at any time. If the client has capacity, they have the right to make their own decisions and to have those decisions respected by their health care providers.5

Physiotherapists seek to understand the client’s values and rationale for their decision and explain their recommendations and concerns to the client while being cautious to avoid coercing the client into the physiotherapist’s proposed course of action.1 They must also seek a solution that respects the client’s autonomy while mitigating any risks related to the client’s chosen course of action.

If the client ultimately decides to follow a course of action that differs from the physiotherapist’s recommendation, the physiotherapist must abide by the client’s decision.5

The physiotherapist’s duty of care to the client requires that the physiotherapist take steps to help the client be as safe as possible within their chosen course of action.

- Evans KG. Consent: A Guide for Canadian Physicians. Available at https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/handbooks/consent-a-guide-for-canadian-physicians#types%20of%20consent Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Ferron-Parayre A, Régis C, Légaré F. Informed Consent from the Legal, Medical and Patient Perspectives: The Need for Mutual Comprehension. Lex Electronica 1, 2017 CanLIIDocs 3940, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/strd Accessed January 31, 2024

- Castel JG. Nature and Effects of Consent with Respect to the Right to Life and the Right to Physical and Mental Integrity in the Medical Field: Criminal and Private Law Aspects. Alberta Law Review 293, 1978 CanLIIDocs 86, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/td5k Accessed January 31, 2024

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Glossary. Draft Standards of Practice for Alberta Physiotherapists.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Informed Consent Standard of Practice. Draft Standards of Practice for Alberta Physiotherapists.

- The Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/ldsx Accessed January 31, 2024

- Tomkins, B. Health Care for Minors: The Right to Consent, Saskatchewan Law Review 41, 1974 CanLIIDocs 241, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/7n3j7 Accessed January 31, 2024

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Patient Centred Communication eLearning Module. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/courses/patient-centered-communication/ Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Canadian Centre for Elder Law (a division of BC Law Institute). Conversations About Care: The Law and Practice of Health Care Consent for People Living with Dementia in British Columbia (full report), Canadian Centre for Elder Law (a division of BC Law Institute), 2019 CanLIIDocs 401, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/sg3s Accessed January 31, 2024

- Reibl v. Hughes, 1980 CanLII 23 (SCC), [1980] 2 SCR 880, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/1mjvr Accessed January 31, 2024

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Information For You: Understanding How Risk is Discussed in Healthcare. Available at https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/sxup5q24/pi-understanding-risk.pdf Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Burningham S, Rachul C, Caulfield TA. Informed Consent and Patient Comprehension: The Law and the Evidence, McGill Journal of Law and Health 123, 2013 CanLIIDocs 36, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/7gp Accessed January 31, 2024

- Schachter CL, Stalker CA, Teram E, Lasiuk GC, Danilkewich A. Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- The Canadian Bar Association. The CBA Child Rights Toolkit: Capacity. Available at https://www.cba.org/Publications-Resources/Practice-Tools/Child-Rights-Toolkit/theChild/Competence,-Capacity-and-Consent Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Government of Alberta. Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act. Available at https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/laws/stat/sa-2008-c-a-4.2/latest/sa-2008-c-a-4.2.html Accessed January 9, 2024.

- Government of Alberta. About Capacity Assessment. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/capacity-assessment Accessed January 8, 2024

- Government of Alberta. Capacity Assessment - Adult Guardianship and Trusteeship Act. Available at https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/7fb814d2-f8c3-4f52-92a7-33af656d9df3/resource/042b083f-9af5-447f-9541-de60a0018260/download/scss-opgt-capacity-assessment-2023.pdf Accessed January 8, 2024

- Government of Alberta. Adult Guardianship. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/adult-guardianship Accessed January 8, 2024

- Government of Alberta. Co-decision Making. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/co-decision-making Accessed January 8, 2024

- Government of Alberta. Trusteeship. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/trusteeship Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Government of Alberta. Personal Directive. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/personal-directive Accessed January 8, 2024

- Centre for Public Legal Education Alberta. Making a Personal Directive. Available at https://www.cplea.ca/wp-content/uploads/MakingAPersonalDirective.pdf Accessed January 8, 2024

- Government of Alberta. Enduring Power of Attorney. Available at https://www.alberta.ca/enduring-power-of-attorney Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Canadian Medical Protective Association. Consent: A Guide for Canadian Physicians. Available at https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/handbooks/consent-a-guide-for-canadian-physicians#Emergency%20treatment Accessed January 8, 2024.

- The College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Good Practice: Legalization of Cannabis. Available at https://www.cpta. ab.ca/news-and-updates/news/good-practice-legalization-of-cannabis/ Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Canadian Pediatric Society. Medical Decision-making in Paediatrics: Infancy to Adolescence. Available at https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/medical-decision-making-in-paediatrics-infancy-to-adolescence Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Government of Alberta. Family Law Act. Alberta King’s Printer: Edmonton. Available at https://kings-printer.alberta. ca/documents/Acts/F04P5.pdf Accessed January 8, 2024.

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Advice to the Profession: Consent for Minor Patients. Available at https://cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AP_Informed-Consent-for-Minors.pdf Accessed January 8, 2024.

- College of Alberta Psychologists. Informed Consent. Available at: https://www.cap.ab.ca/Portals/0/pdfs/New%20 Guidelines/Practice%20Guideline-%20Informed%20 Consent.pdf?ver=2019-08-20-102058-527 Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Alberta Health Services. Summary Sheet: Consent to Treatment/Procedures Minors/Mature Minors. Available at https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hpsp/if-hpsp-phys-consent-summary-sheet-minors-mature-minors. pdf Accessed January 8, 2024.

- Provincial Health Services Authority. Interpreting. Available at http://www.phsa.ca/our-services/programs-services/provincial-language-services/interpreting#Language--interpreting Accessed January 8, 2024.