Effective therapeutic relationships lead to increased patient satisfaction, better patient adherence to treatment plans, and improved patient outcomes. A physiotherapist’s awareness of how to establish and maintain healthy therapeutic relationships is essential to clinical practice.

Therapeutic Relationships Guide PDFPhysiotherapists are involved in multiple therapeutic relationships each day. But what defines the therapeutic relationship? The therapeutic relationship entails “an interactive relationship with a client and family that is caring, clear, positive, and professional.”¹ Each and every client relationship includes a process of building a therapeutic relationship and then maintaining that relationship through the ups and downs of clinical care. Therapeutic relationships often extend to include the client’s family, guardian, caregiver, and others. The requirement to develop and maintain effective therapeutic relationships is established in the Code of Ethical Conduct2 and the Standards of Practice for Alberta Physiotherapists.3

The intent of this guide is to provide a more in-depth look at therapeutic relationships with tips and suggestions for the physiotherapist. The guide will use common situations that come up in practice to explore the goals of the guide, which include:

- Exploring the foundations of a positive therapeutic relationship.

- Creating appropriate professional boundaries.

- Finding a balance between personal and therapeutic relationships.

Guides are intended to advise those accessing them, but a physiotherapist’s situation may have context that isn’t captured in a guide. To assist the reader, this guide will employ scenarios from physiotherapy practice to highlight key concepts.

Note that additional supports regarding therapeutic relationships, professional boundaries and managing challenging situations are available from the College of Physiotherapists of Alberta.

It takes dedicated time, energy, and skill to consistently build positive therapeutic relationships. This section will explore the Pillars of a Positive Therapeutic Relationship4 and the ATTACH method5: two fundamental approaches one can use to build a positive therapeutic relationship with clients and others involved in their care.

Vignette:

Cassi has had difficulty trusting health care providers. During her teens, she and her mother spent some time unhoused and living in their vehicle. Due to her circumstances, she has felt that doctors and other health care professionals were dismissive and rude to her. She has been battling a knee infection and has visited Radek, a physiotherapist, to help her get walking and back to work. Radek takes the time to actively listen to her concerns and frustrations. He has attempted to demonstrate empathy and make Cassi feel heard. Over the course of several visits, she was improving but then missed her last appointment and has not been in touch for 3 weeks. What should Radek do?

Pillars of a Positive Therapeutic Relationship

There are many different versions of what creates and maintains a positive therapeutic relationship. According to research from Miciak, et. al., the basic pillars include the physiotherapist being4:

- Present – physiotherapists work in practice settings that can be fast-paced, where time and resources are limited. The ability of the physiotherapist to be “present” and engaged with their clients is important. Clients can perceive when a physiotherapist is distracted or more concerned about “the time” than the client.

- Receptive – physiotherapists who can accept the client for who they are and appreciate the values, characteristics, and lived experiences that are part of the client’s identity are better able to form positive therapeutic relationships. Active listening is a large part of developing this pillar and allowing the client to tell their story and feel heard. Creating a feeling of “focused receptivity” by recognizing the client’s verbal and non-verbal cues will allow the physiotherapist to gain insight into the client and will enhance a sense of positivity from the client towards the physiotherapist. These are actions the physiotherapist can take to demonstrate that they value the client and the client’s story. The physiotherapist should also be aware of their own body language and what that conveys to the client.

- Genuine – client interactions should be sincere. Although focused on maintaining professional boundaries, the physiotherapist should be themselves when interacting with clients. Having a real personality will help to build the therapeutic relationship, but the physiotherapist should be mindful and intentional of what they choose to share with the client. Honesty is a component of the Code of Ethical Conduct2 and helps the physiotherapist gain the client’s trust. However, there must be clear boundaries of what is being shared and the purpose for sharing.

- Committed – physiotherapists can be committed to understanding the client by investing the time, energy, and focus needed to get to know them. A physiotherapist who consistently works to get to know the person who is in front of them and continually puts forth the effort needed to create positive therapeutic outcomes shows they are committed to that client. Keeping to the 3 other pillars discussed above will contribute to the overall commitment of the physiotherapist to understand the client.

The ATTACH Framework

Another framework drawn from the field of mental-health nursing, but applicable to physiotherapy practice is the ATTACH framework.5

| Authentic | Being authentic with clients is crucial, since physiotherapists are their own instruments of care, and they use themselves in practice. |

|---|---|

Trustworthy |

Being a reliable and well-informed professional encourages clients to build trust in their physiotherapist, their judgement, and their practice. |

Time-Maker |

Making focused time to be with clients makes them feel cared for and listened to and enables a physiotherapist to discuss the timeframe of care, including plans for when the therapeutic relationship will end. |

Approachable |

Being approachable and visible, being a good listener, and providing empathetic responses is vital. |

Consistent Communicator |

Communication is crucial. Physiotherapists need to provide a consistent message to the client from themselves and the multidisciplinary team. |

Honest |

Honesty is a fundamental value of the physiotherapy profession and enables physiotherapists to have open and realistic conversations with clients. |

Vignette Continued:

Radek reaches out to Cassi to check in and see if she is managing well. She admits she isn’t doing well and is grateful that he called. She decides to get back to physio and after 3 more visits, she is successfully discharged. On her last visit, Cassi expresses how grateful she is that Radek took the time to check in on her and for the way he listened to her over the course of their time together.

There is much research that has shown how effective a positive therapeutic relationship can be on a client’s outcomes including both client satisfaction and clinical outcomes.6-11 Most physiotherapists can identify times when a positive therapeutic relationship has been essential for helping to achieve a client’s goals and other times when a negative relationship has contributed to poor outcomes of care.

Vignette:

Marina has been working with Joren for the past 4 weeks following his total hip replacement. Joren’s wife, Brianna has been attending appointments and has been critical of Marina’s care thus far. Marina is not sure of the source of the issue with Brianna, but she does recognize how Brianna’s disapproval is impacting her ability to create a positive therapeutic relationship with Joren. At their next session, Joren admits he has been less inclined to follow the exercise protocol. She realizes that the failure to develop a positive relationship with Joren and Brianna has led to a decline in adherence to his post-op protocol and is negatively affecting his progress. What should Marina do to salvage this relationship?

Although it can be challenging to spend the time and energy cultivating a positive therapeutic relationship, the extent of the research into this area would indicate it is a foundational step to achieving consistent success with clients. It has also been demonstrated that many of the qualities that clients feel represent ‘good’ physiotherapy contain overlapping themes to a positive therapeutic relationship.10 The qualities of a ‘good’ physiotherapist include:

- Responsive

- Ethical

- Communicative

- Caring

- Competent

- Collaborative

“The overarching conclusion is that a ‘good’ physiotherapist balances technical competence with a human way of being when interacting with patients.”10

However, physiotherapists can also see how a negative therapeutic relationship can lead to poor outcomes. In the vignette above we can see how a negative therapeutic relationship can affect client care and outcomes.

Vignette Continued:

Marina makes the decision to sit down with Brianna and Joren and have a conversation about their therapeutic relationship. She outlines her goals for the discussion and the main points she wants to cover prior to having the conversation. She also considers some of the potential barriers or stressors Joren and Brianna may be experiencing that may be leading to this issue. During the meeting, Marina discusses her concerns and gives Joren and Brianna time to consider their response. As they talk Marina gives them both the opportunity to discuss any issues that may be contributing to the negative working relationship. The conversation is difficult and awkward at times, but Marina can discuss her concerns and gains insight into Joren and Brianna’s perspectives. She gives Joren the option to continue his care with another physiotherapist or to continue to work with her. In the conversation, she outlines a plan for how they can work together to improve his post-surgical outcomes. She reviews some potential options for different approaches they could try that might work better for Joren and after discussing it with Brianna, Joren thinks it best that they continue to work with Marina.

Physiotherapists have relationships with clients, peers, staff, management, and others that arise from their role as a physiotherapist. Physiotherapists may also develop a level of camaraderie with their clients. Physiotherapists are not robots and as already discussed, it can be beneficial when physiotherapists develop strong therapeutic relationships with their clients. This may involve the physiotherapist being personable and intentionally disclosing information about themselves.

However, as therapeutic relationships develop, it is important to keep the distinctions between personal and therapeutic relationships in mind and be attentive to maintaining professional boundaries. This section will discuss the distinctions between personal and therapeutic relationships, what a professional boundary is, and warning signs of blurred boundaries and boundary violations.

Prior to engaging in a therapeutic relationship, the physiotherapist must acknowledge that:

- There is an inherent power imbalance in the physiotherapist-client relationship. There may be situations where the power imbalance varies in degree depending on the nature of the relationship, identities, and lived experiences of the people involved. However, due to the knowledge and skills of the physiotherapist and the patient’s inherent vulnerability to requiring health care, the physiotherapist has greater influence and is in a position of power relative to the client.

- The physiotherapy profession has expectations for appropriate behaviour. Expectations come from existing legislation, the Standards of Practice and the Code of Ethical Conduct. When issues or concerns arise, an important benchmark is to consider what a group of peer physiotherapists would consider reasonable or appropriate.

- The physiotherapist has a duty of care. Their responsibility to the client is to ensure that the client is receiving the care that they need. The purpose of the therapeutic relationship is to ensure that the patient’s needs are addressed. If the focus of the relationship shifts to addressing the physiotherapist’s needs, problems arise.

In situations where a therapeutic relationship has been damaged and a physiotherapist is unable to provide care due to an unrepairable therapeutic relationship, the physiotherapist must, as part of their duty of care, assist the client in finding access to ongoing care elsewhere.

Vignette:

Yui works within a rehabilitation facility with people who have had amputations. Yui has been treating Pat for several weeks. Their conversations have strayed to more personal topics and Yui has recently been spending time outside of work hours with Pat to meet them for lunch in the cafeteria. Pat and Yui have been sharing stories from their dating lives and Yui makes a joke to Pat about her social awkwardness on dates. Yui meets with Pat later for a treatment session and realizes Pat is upset and tells Yui that they do not want to continue treatment today. Yui thinks it might have been the joke that upset her. How could Yui have prevented the situation? Was it appropriate for Yui to meet Pat for lunch?

Therapeutic Relationships vs. Personal Relationships

Consider the elements of relationships and the distinctions between therapeutic relationships and personal relationships outlined in the table below.12-13

Relationships are not always neatly divided into therapeutic and personal or appropriate and inappropriate. Although the table presents the elements of personal and therapeutic relationships as being distinct and dichotomous, in practice relationships often exist on a continuum from therapeutic to personal. With each relationship dimension, grey zones can exist and context matters.

Sometimes it can be difficult to know where the tipping point is between a relationship that is therapeutic and one that has become personal. However, the probability of a boundary violation increases when a therapeutic relationship shifts from the formal, professional end of the relationship continuum towards a relationship that is more informal or personal in nature.

| Therapeutic Relationship | Personal Relationship | |

|---|---|---|

Time-limited and related to a client’s need for physiotherapy services. |

LENGTH OF RELATIONSHIP |

May last a lifetime. |

Limited to where physiotherapy services are required or provided. |

LOCATION OF RELATIONSHIP |

May occur anywhere. |

To meet the physiotherapy needs of the client. |

PURPOSE OF THE RELATIONSHIP |

Directed by camaraderie, personal, or self-interest. |

Unequal power favors the physiotherapist due to professional skill and access to the client’s personal information. A misuse of power is considered abuse. |

POWER BALANCE |

Relatively equal power affected by a variety of factors and may shift depending on the situation. |

Defined by the length of the physiotherapy session and the nature of the care required. |

STRUCTURE |

Spontaneous and unstructured. |

The physiotherapist is responsible for establishing and maintaining the therapeutic relationship and professional boundaries. |

RESPONSIBILITY FOR RELATIONSHIP |

Equal responsibility to establish and maintain the personal relationship. |

The physiotherapist receives money to provide client care. |

FINANCIAL |

Financial obligations may be shared. |

Critical to the formation of the therapeutic relationship. |

TRUST & RESPECT |

Changes depending on the type of relationship. |

Professional touch is inherent to physiotherapy services. |

TOUCH |

Personal or social touch (e.g., hugs) may or may not be present. |

Defining Professional Boundaries

Boundaries refer to the accepted social, physical, or psychological space between people. Boundaries create an appropriate therapeutic or professional distance between the physiotherapist and another individual and clarify their respective roles and expectations.11

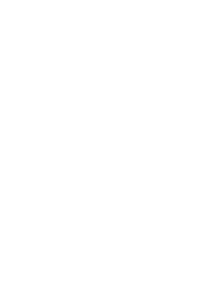

Professional boundaries create the container which a therapeutic relationship can be built within.

Vignette Continued:

Yui’s actions led to a blending of her personal and professional life. She allowed behaviours and conversations to stray from professional to more personal. The decision to meet Pat for lunch has further shifted the relationship from therapeutic to personal. The blurring of professional boundaries and shift in the nature of the relationship led to a negative effect on Yui’s therapeutic relationship with Pat. Yui now needs to take steps to reestablish a positive therapeutic relationship and professional boundaries with Pat so that physiotherapy sessions can resume. How Yui does so will be addressed later on.

In an ideal situation, boundaries are clearly defined. In reality, they can become blurry. Rather than a clearly delineated line, there can be a grey zone between what’s appropriate to a therapeutic relationship and what is not. Although there is often consensus regarding actions, comments, and behaviours that are clearly inappropriate to the therapeutic relationship, the actions, comments, and behaviours that fall within the grey zone can depend on the individuals involved in the therapeutic relationship, the services provided, and the context in which the physiotherapy services are delivered.

The boundaries that exist with a client are different than the boundaries that exist between colleagues and peers, due to the differences between working relationships and therapeutic relationships. However, power can be a factor in both types of relationships. The purpose of this guide is to focus on the therapeu-tic relationship between the physiotherapist and the client, but it is important to recognize that the informa-tion can be applied to other professional relationships such as those between physiotherapists and their colleagues.

Managing Self-Disclosures

As part of building a therapeutic relationship with the client and delivering client-centered care, it is important for the physiotherapist to get to know the client, the client’s goals, and their values. It can be helpful for the physiotherapist to share some of their own life story and relatable experiences with the client to strengthen the therapeutic relationship and facilitate client trust and disclosure.

While personal disclosures can facilitate the development of the therapeutic relationship, the physiotherapist must be thoughtful about the information they share and the intent and purpose of that disclosure.

Self-disclosures are employed intentionally and for the purpose of developing the therapeutic relationship and not for the purpose of developing personal relationships. Self-disclosures must not undermine professional boundaries or shift the relationship from being a therapeutic relationship to a personal one.

Personal disclosures always pose the risk of blurring the boundaries between personal and therapeutic relationships. Physiotherapists must monitor their interactions, engage intentionally with their clients, and practice self-reflection regarding their actions, interactions, and use of personal disclosures within therapeutic relationships.

Vignette:

Sunny is a newly graduated physiotherapist intern working at a small private practice clinic. Sunny has been treating Jodie for the past 2 months after a workplace accident. Jodie and Sunny get along well and are constantly chatting about Jodie’s injury, work, and their lives outside of work and physiotherapy. Sunny has been happy with Jodie’s progress thus far and is finishing up a progress report. Jodie notices that Sunny has suggested that they are ready to return to work on modified duties and their symptoms and scores on functional outcome measures have signifi-cantly improved. Prior to their injury, Jodie was unhappy at work. Sunny has identified that there may be some barriers to Jodie returning to work that don’t relate to their injury. Despite the positive changes in their condition, Jodie is hoping Sunny will change the report to give them some more time away from work. They approach Sunny to have him change the report. What should Sunny do?

When boundaries become blurred, or therapeutic relationships shift towards more personal relationships, it can lead to situations where the physiotherapist finds that their objectivity and professional judgement can be affected. Physiotherapists must avoid situations where their professional judgment is compromised. This includes situations where their judgment is compromised due to their personal relationship with a client. In instances where a physiotherapist recognizes that the relationship has shifted away from a therapeutic relationship and has strayed into the blurry, grey zone between therapeutic and personal relationships, they must take action to reinstate professional boundaries and must guard against their judgment becoming compromised.

Vignette Continued:

Sunny empathizes with Jodie’s work dissatisfaction and generally has a positive impression of Jodie, but he recognizes he has a professional responsibility to uphold. Sunny’s opinion as a primary health care provider should not be influenced by Jodie’s wishes or the sympathetic feelings Sunny has towards Jodie. Even though Sunny may have enjoyed his time working with Jodie he cannot allow his professional opinion to be influenced by Jodie’s request or the nature of their relationship. Sunny reviewed Jodie's job duties and the goals that he and Jodie established at the initial assessment. Sunny compared these with the most recent outcomes Jodie has demonstrated and asked Jodie’s thoughts on unmet goals. Sunny reinforced that his professional responsibilities are to be truthful and accurate in any reporting that they are required to complete.

Blurring Boundaries

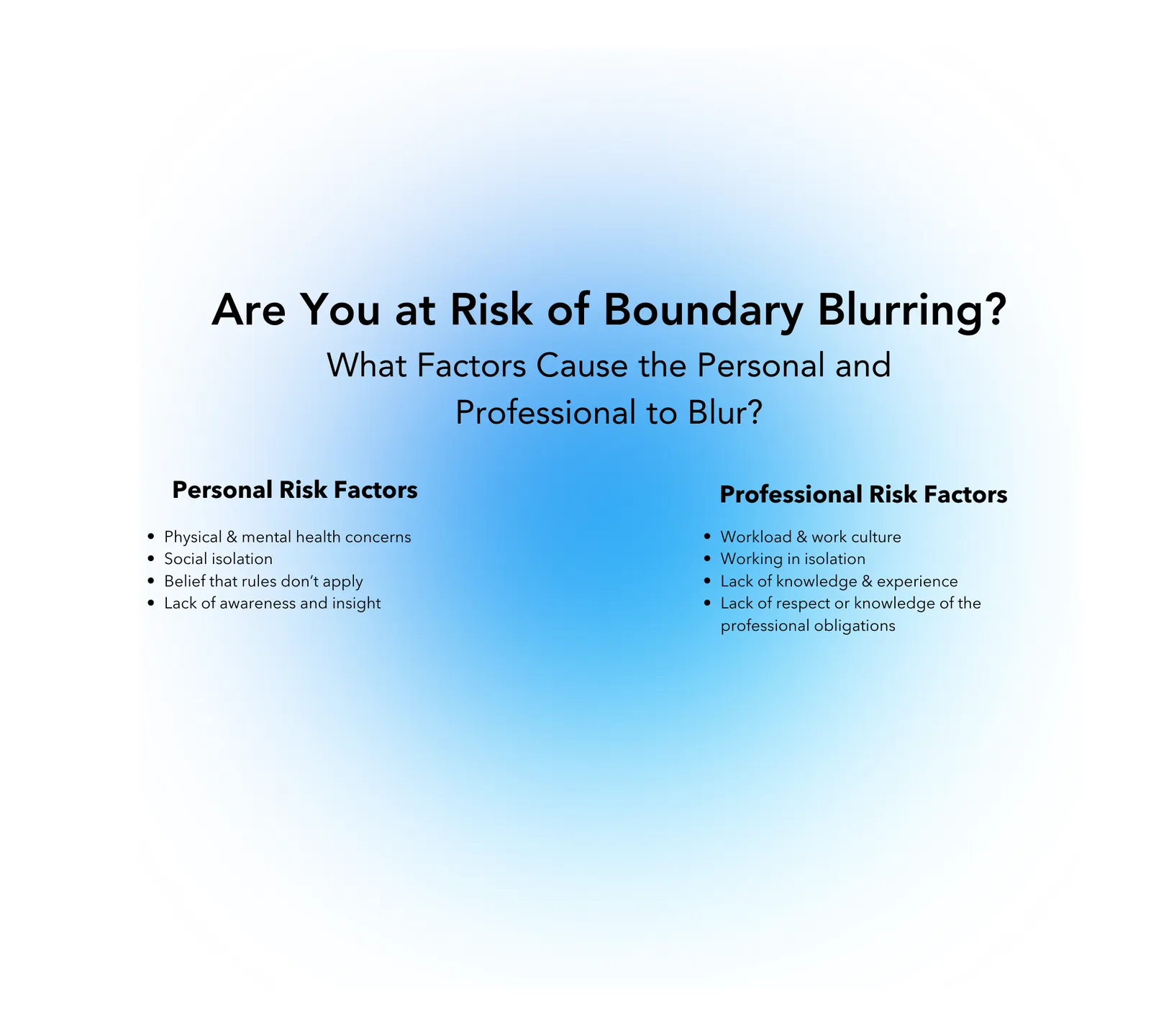

Professional boundaries exist to create a safe space for physiotherapy service delivery. The interactions between clients and physiotherapists should always be professional, with the focus of the interactions on achieving the client’s goals. The initial boundaries that are established to create the container in which the therapeutic relationship can be built can occasionally start to blur. As boundaries blur the risk of a boundary violation increases and that begins to put stress on the therapeutic relationship. The blurring of boundaries exists on a spectrum or gradient and it is often within the physiotherapist’s capacity to redirect the relationship back to appropriate professional boundaries when they notice that a boundary is being blurred. Physiotherapists should also consider the personal and professional factors that may put them at risk of blurring or violating a professional boundary.

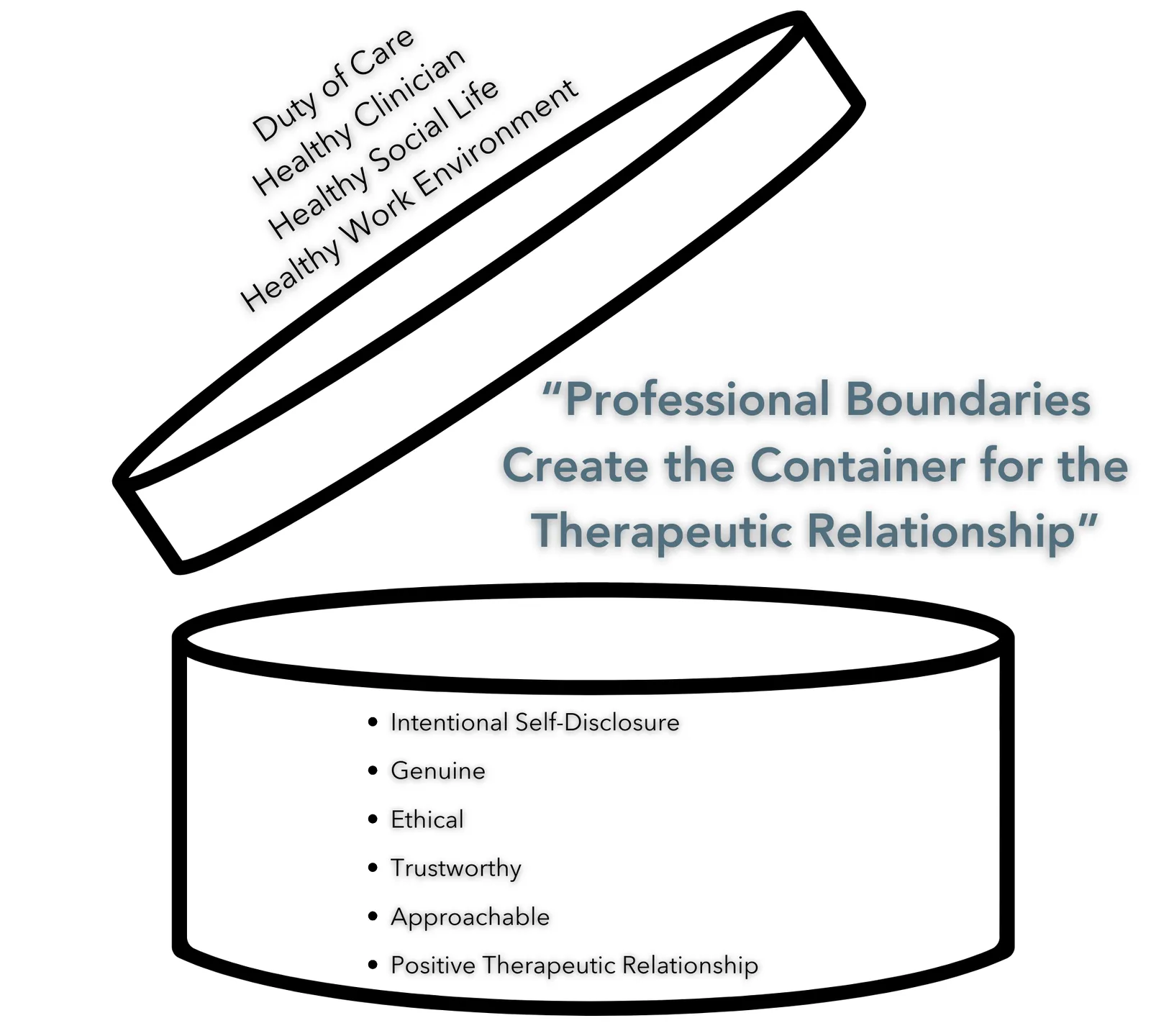

What Puts a Physiotherapist at Risk of Blurring or Violating a Boundary?

Personal and professional factors can increase a physiotherapist’s risk of engaging in questionable or inappropriate behavior.

Personal factors can include14:

- Physical and mental health concerns, including stress or burnout.

- Social isolation. Feelings of loneliness or lack of a positive social network outside of work.

- Belief that the rules ‘don’t apply to me’ or to the situation at hand.

- Lack of awareness and insight regarding the culture of the population served, and failure to apply appropriate, culturally sensitive care.

Professional factors can include14:

- Workload or other system factors.

- Working in isolation (either as sole charge practitioner or due to team dysfunction resulting in isolation).

- Lack of knowledge or respect for the Standards of Practice and other professional obligations.

- Lack of clinical knowledge or experience (new to the area of practice or failing to maintain currency of knowledge).

Warning Signs for Blurring or Violating a Boundary

Boundary violations can result from a single incident, however, most often they arise because of the cumulation of a series of decisions or actions that first blur and then ultimately violate the professional boundaries in a therapeutic relationship. The blurring of boundaries usually comes with warning signs that can indicate a change in a physiotherapist’s actions and relationship with the client.15-17 Some warning signs include:

- Scheduling more time/sessions than what is typical to meet therapeutic goals.

- Providing preferential treatment based on looks, age, or social standing.

- Accepting personal invitations, either online or in person.

- Sharing excess personal information, or personal problems with a client.

- Dressing differently when seeing a particular client.

- Frequently thinking about or communicating with a client outside of the context of the therapeutic relationship.

- Being defensive, embarrassed, or making excuses when someone comments on or questions a physiotherapist’s interactions with a client.

- Providing the client with personal contact information

- Providing and accepting gifts.

- Having more physical contact than is required or appropri-ate for clinical care.

- Involvement with a client’s family members outside of the therapeutic relationship.

Re-Establishing Blurred Boundaries

Vignette:

Karl is a pediatric physiotherapist who has been treating a client with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. He is out at the park on the weekend when he is approached by the client’s mother. They get into a lengthy discussion about the child, their needs, and some suggestions for upcoming treatment sessions and potential letters for funding. Karl is trying to end the conversation but is having a difficult time doing so. The conversation moves to more personal matters and Karl is asked if he wants to meet her later for a drink.

Boundaries can be blurred by both the physiotherapist and the client. The physiotherapist is the professional and has a responsibility to keep the therapeutic relationship positive and within the confines of physiotherapy services and professional expectations. However, the client can exert pressure on the physiotherapist to move the therapeutic relationship towards a more personal one.

Vignette Continued:

Karl kept his conversation professional and was surprised by the offer to get a drink later. He politely thanks the client’s mother for the offer but emphasizes that he cannot accept the invitation due to his professional role and responsibilities.

The extent to which boundaries are blurred can vary. Sometimes it is easy to catch a slip-up and make a correction with a client as Karl did with his client’s mother. In other cases, the therapeutic relationship could be unrepairable, and the client may need to be transferred to another physiotherapist, as may be the case with Yui and Pat. Listed below are some actions a physiotherapist can take when faced with boundary blurring or a boundary violation:

- Reflect on the client relationship and examine the actions that occurred and the intent behind them.

- Talk about the situation with trusted colleagues and ask for feedback.

- Take steps to re-establish the appropriate boundaries with their client.

- Explain, in a client-focused manner, that the focus of the therapeutic relationship has shifted away from meeting the client’s health care needs and must be corrected.

- • Clarify their role as a physiotherapist and appropriate boundaries going forward.

- Stop interacting with the client outside of time spent treating them, both in person and online.

- Maintain focus on the client’s health care needs during continued interactions.

- Be prepared to balance social conversations and getting to know the client better (discussing hockey, movies, the client’s pet, etc.) with client care. Are the social conversations detracting from the focus on the client’s goals? The physiotherapist should ask themselves if the client is still the focus and redirect the discussion.

- If boundaries cannot be re-established, the physiotherapist must withdraw from or end the therapeutic relationship by transferring care to another appropriate care provider.

Yui’s Vignette Continued:

Yui recognized that their comments caused a rift in their therapeutic relationship with Pat. On further reflection, they also realized that meeting Pat for lunch was inappropriate and that by doing so Yui had shifted the nature of the relationship away from a therapeutic one to being more personal in nature. Yui arranges a meeting to speak with Pat. Prior to the meeting, Yui takes some time to read the Managing Challenging Situations Guide and plans the conversation in advance. She considers the potential outcomes of the conversation and what approaches she should take to help mend the therapeutic relationship. At the meeting, Yui apologizes to Pat for her comment. Yui lets Pat know that Pat’s physiotherapy is the priority and in the future Yui will keep the relationship professional. She reestablishes boundaries for conversations when they are together, and they agree that the time spent together will be focused on Pat’s rehabilitation. Yui explains that she will no longer meet Pat for lunch as it is not an appropriate part of a therapeutic relationship.

A boundary violation results from an action that harms the nature of the therapeutic relationship and creates a negative outcome for the client or negative feelings. Boundary violations can occur on either side of the therapeutic relationship and can be intentional or unintentional. Regardless, it is the physiotherapist’s responsibility to address the situation and re-establish the therapeutic relationship or take appropriate action to transfer the patient’s care to another physiotherapist if they cannot.

In this section, we will discuss common situations in professional practice that can result in boundary violations, including gifts, social media use, and touch and what actions a physiotherapist should take if they have violated a professional boundary.

Gifts

In general, accepting gifts is part of a personal relationship, not a therapeutic relationship. Accepting a gift from a client may create a sense of obligation to provide a specific treatment or benefit to the client or may compromise the physiotherapist’s clinical judgement. Accepting gifts always carries some degree of risk and may or may not constitute boundary blurring or a boundary violation.

Context is everything.

Vignette:

Gabrielle has been treating Jasmine, a WCB client, for the past couple of weeks. So far treatment has gone well, and Jasmine is improving. Jasmine shows up at their next ap-pointment with a tray of homemade cookies for the staff and a $100 gift card for Gabrielle. Jasmine expresses their happiness with treatment so far and that they feel that since their treatment is covered by WCB, they owe Gabri-elle something extra.

A physiotherapist should ask themselves:

- What motivated my client to offer this gift?

» The potential desire for a ‘special relationship,’ or future preferential

treatment, increases the risk of accepting a gift.

- Did I say something (i.e., mention my upcoming birthday) that made the client feel obligated to bring the gift?

- How will accepting the gift impact my ability to make objective, unbiased clinical decisions?

- Could another person perceive that accepting the gift constitutes fraud or theft, or be a result of manipulation?

| Less Risk | More Risk |

|---|---|

Token value |

Valuable (monetary or meaningful) |

For a group |

To an individual |

"Thank you" at discharge |

During the course of treatment |

Spontaneous |

Solicited |

Edible/Shareable |

Person specific |

Private pay patient |

Third-party insured patient |

It is always up to the physiotherapist’s discretion to accept or decline a gift. If it ‘feels wrong,’ take that as a sign it would be best to graciously decline the gift. Consider developing strategies that discourage gift-giving. An example would be developing and communicating policies that make it clear what a physiotherapist will do with any gift, such as donating all monetary gifts to charity or placing consumable gifts in a staff room. This may help to minimize the pressure to give or accept gifts.

Vignette Continued:

Gabrielle tells Jasmine that it is not necessary to provide any gifts and that she cannot accept the gift card. Gabrielle is very appreciative of the cookies that Jasmine made for the staff. She happily accepts the cookies on behalf of the clinic.

Gifts with a monetary value directed at a specific clinician and from a client who is currently under care covered by a third-party provider pose a risk that the gift could be seen to have influenced the physiotherapist’s judgement and ability to remain unbiased. It is wise to decline gifts that have a monetary value as ultimately the third-party payer could question the physiotherapist’s objectivity and the accuracy of their reporting, potentially harming both the patient’s claim and the physiotherapist’s professional reputation. While gifts of a monetary value may carry less risk when the client is paying out of pocket for services or is receiving publicly funded treatment, accepting a gift in these contexts may still create a perception that the physiotherapist owes the client special favors in return, such as additional publicly funded treatments or improved access to appointments.

Social Media

Social media use and the number of concerns and complaints related to social media are increasing across the professional landscape.16 Physiotherapists should be aware that their personal and professional use of social media can lead to accusations of unprofessional conduct and boundary violations. Below is a list of risks related to social media use by physiotherapists.

- Posting personal content on a professional page is often used to “humanize” the professional but can lead to a blurring of professional boundaries.

» Blending personal and professional lives online enables client access to

personal information.

» Easy access to a physiotherapist’s personal and professional accounts by

clients, peers, and potential employers can allow others to access information

the physiotherapist ought to keep or may wish to keep private.

- When a physiotherapist chooses to “friend” a client, it can create the potential for the client to become too personal with the physiotherapist in their treatment sessions. It can also lead the patient to perceive that they have a ‘special’ relationship with the physiotherapist and alter their expectations of the physiotherapist.

- Online interactions between the physiotherapist and client can lead to a failure to prioritize the client’s reason for accessing physiotherapy services and instead spend time discussing more personal topics.

For more information on the professional use of social media, please access the College’s Social Media Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists.

Touching in Clinical Practice

Inappropriate touching is any form of physical contact that is not clinically indicated or is otherwise unwanted by the client16; this includes both touching of a sexual nature and other forms of touching.

Vignette:

Omar is a physiotherapist working in a private clinic and has a client named Dave who has been attending physiotherapy sessions for some time. Omar and Dave have a good therapeutic relationship and Omar has lots of empathy for Dave. Dave has previously disclosed to Omar that they are having some major stressors in their home life which are affecting their ability to attend appointments. Today, while talking to Omar, Dave starts to cry and ap-pears distraught. How should Omar respond? Should Omar offer Dave a hug?

Touch is a key aspect of physiotherapy service delivery. Physiotherapists employ many different assessment and treatment techniques that require physical touch and close contact. A physiotherapist may move a client’s legs and arms, transfer them from a chair to a plinth, and generally work in close proximity to the client all the time. Due to the frequency with which physiotherapists employ client handling they can become complacent in how they employ touch in practice.

What Should a Physiotherapist Do Prior to Touching a Client?

- Receive informed consent to the assessment or treatment techniques they are employing.

- Ensure the client knows they can withdraw consent at any time.

- Provide suitable privacy and draping during an examination or treatment.

- Never assume a client knows what the physiotherapist is intending to do.

- Provide clear information suitable for the client’s level of understanding.

Touch in physiotherapy practice exists on a continuum:

If a physiotherapist fails to clearly explain the reason for touching the patient and fails to gain informed consent prior to making physical contact with a client, this action could form the basis for a complaint about the physiotherapist’s practice. It does not matter what body part the physiotherapist was touching or the physiotherapist’s intentions or perception of what occurred; it is the client’s perception of the conduct that matters.

What about Physical Contact Intended to Provide Emotional Support?

Touch as part of providing emotional support is different from touch as part of physiotherapy service delivery.

Physical contact with a client for non-clinical reasons, such as a gentle pat on the back or a hug should be carefully considered against the potential risk the client might find the gesture unwanted, intrusive, or inappropriate. The physical action of the physiotherapist carries the potential of either a positive or negative effect on the therapeutic relationship. The clinical context and the physiotherapist’s existing relationship with the client matter most in these scenarios. Is the physiotherapist sure they know this client, their perspective, and how they will react? Generally, it is best to avoid non-clinical physical contact. If a physiotherapist decides they are going to give a hug or pat on the back, they must realize that they are taking a risk that the client may not receive the hug as it was intended and must consider their actions accordingly.

Vignette Continued:

Omar knows that touch as part of giving support is different from touch that is essential to physiotherapy service delivery. He lets Dave know it is ok to be upset. Omar leaves the room to get Dave tissues and to give him time and space to regain his composure. Omar voices his support, acknowledging that Dave has a lot going on, but that they are showing progress. He works to instill hope. Omar considered offering Dave a hug because he has known him for a long time and they have a good relationship but ultimately decided that that would not be a good idea because of the stressors Dave has identified in their home life and his concern that the gesture may be misinterpreted.

Offering a hug carries more risk than other forms of touch intended to provide emotional support because a hug could be perceived as sexualized or more intrusive to the client’s personal space. Physiotherapists should carefully consider the context and their own personal feelings and motivations before touching or embracing a client to provide emotional support.

What is a Close Personal Relationship?

A close personal relationship is a relationship where the physiotherapist’s ability to be objective and impartial to fulfill their professional obligations may be impaired due to the personal relationship. Close personal relationships typically exist between a physiotherapist and their spouse or partner, family members, business partners, colleagues, past romantic partners, and close friends.

Vignette:

Maurice is a physiotherapist working with a support worker, Sascha, in a private clinic. They have been working together for a few years and know each other quite well. As Maurice is taking his lunch break Sascha approaches him complaining of a sore neck that they woke up with that morning. Sascha asks Maurice if they could perform some needling on them to help them out. Maurice feels a duty to help Sascha because of their long-standing work relationship. He doesn’t have enough time to do a full assessment but decides that he can squeeze in a quick history and then needle Sascha's upper trapezius and mid-back.

Is it a Close Relationship?

The College often hears from physiotherapists who struggle to distinguish individuals they know from those individuals with whom they have a close personal relationship. As already stated, context matters when considering these questions, but the simple fact that when a physiotherapist knows or has met someone previously does not mean that they are in a close personal relationship.

To decide if a close personal relationship exists, a physiotherapist needs to consider whether their professional judgment, ability to be objective and impartial, and ability to fulfill their professional obligations may be impaired by the nature of the personal relationship with their client.

Consider the following elements of personal relationships:

| Close Personal Relationship | Acquaintance | |

|---|---|---|

Personal Knowledge |

High Risk – They are closely involved in the person’s life. |

Low Risk – They know some but not much about the details of the person’s life. |

Time Spent Together |

They spend frequent time with the person sharing friends, housing, or activities. |

They see the person occasionally and may share friends or occasionally do activities together. |

Connection |

They have close association with the person through work or family. |

There are distant associations through work or family. |

Personal Interest |

Either party has a desire to please the other person. |

There is no personal interest between the physiotherapist or the client. |

Level of Physical Intimacy |

They currently have a sexual relationship with the person |

They do not or have ever had a sexual relationship with the person. |

Level of Emotional Intimacy |

The client is someone the physiotherapist confides in, seeks support from, or has emotional attachments to. |

The client is someone they have casual conversations with, and encounters are generally brief and superficial. |

Power Imbalance |

The relationship is close enough that one may hold power over the other financially, socially, romantically, or in terms of authority. |

The relationship is distant enough that any perceived power imbalance is insignificant. |

Financial Connections |

There are shared business dealings or are connected to each other financially. |

There are no financial ties to the client. |

What are the Risks?

When a close personal relationship exists, the issue is that the physiotherapist’s objectivity and clinical judgement could be compromised by the relationship. What are the potential risks?

- The physiotherapist’s ability to be objective may be compromised.

- Other parties may question the accuracy or truthfulness of the physiotherapist’s documentation and reports, negatively affecting the client’s access to funding and support they would otherwise be entitled to.

- The physiotherapist may make assumptions instead of asking thorough questions or conducting a comprehensive assessment.

- The client may not want to answer questions honestly (due to the potential for embarrassment, or not wanting to hurt the physiotherapist’s feelings if they are not improving or are not following the physiotherapist’s recommendations).

- Documentation of assessment and treatment findings may not adhere to regulatory standards.

- The personal relationship may suffer if the therapeutic relationship is not successful.

Can a Physiotherapist Treat Someone with Whom they have a Close Personal Relationship?

Due to the risks listed above it is recommended that the physiotherapist refrain from treating someone with whom they have a close personal relationship when there are reasonable alternatives available. If there are no reasonable alternatives, the physiotherapist may proceed in treating the person with whom they have a close personal relationship. Examples include living remotely or other physiotherapists in the community not having the competence to treat a specific injury or condition. However, if they choose to do so they must:

- Fully disclose and document the conflict of interest to the client and other relevant stakeholders indicating how the therapeutic relationship is to the client’s benefit and com-plies with regulatory requirements.

- Follow formal processes for consent, assessment, treatment planning, billing, and other aspects of service delivery, and document all physiotherapy services provided.

- Document in a complete, open, and timely manner how the conflict of interest was managed.

Remember that third-party payers may have rules about whether a physiotherapist can bill for providing treatment to an immediate family member, co-worker, or employee. Contact the insurer directly to enquire about any such provisions within their policies.

Vignette Continued:

Several weeks pass by and Sascha comes to Maurice complaining of persistent pain since he treated her. Sascha thinks it is due to Maurice’s treatment. Sascha is blaming Maurice for the issue and has threatened to file a complaint. Unfortunately, Maurice didn’t create a chart note to support any of the services provided or their assessment. Nothing indicates that he appropriately assessed Sascha prior to applying the treatment. There is no consent documentation for the assessment or dry needling. Maurice is now facing a very risky situation if Sascha decides to file a claim or make a complaint to the College.

As previously pointed out, not everyone a physiotherapist interacts with or knows outside of work is considered a close personal relationship. However, individuals who are members of small communities may wonder how they can live and work within a community where they potentially know everyone.

Living in a small town means that a physiotherapist may interact with their clients in their day-to-day lives outside of clinical practice. However, small communities also exist within urban centres in the form of religious communities, local community service groups, and recreational sports leagues. Given that small communities exist in both rural and urban centres, both should be considered when talking about how to manage close personal relationships. How does a physiotherapist navigate their professionalism and privacy as a member of a small community?

Informal Physiotherapy Consultations

Vignette:

Eeson has recently returned to his hometown to begin his physiotherapy career. The town has less than 2000 residents so most of the locals know him well from when he was growing up and through his family who still live in town. He notices within the first couple months of being back home that he gets approached in the grocery store or on the street by clients about their injuries or issues. He knows these people and wants to help them but isn’t sure how he should deal with those who approach him outside of the clinic.

One of the issues commonly encountered by physiotherapists working in small communities is the “screen door” or “grocery store consultation”. Like social media “consultations”, physiotherapists don’t have the ability to get sufficient information from the person, go through an objective assessment, or document the interaction arising in these types of informal settings. Therefore, informal assessments should not be happening. Physiotherapists are advised to come up with some consistent phrasing or messaging to those who approach them expecting advice or an answer. Some examples of phrasing are found below.

“Oh, I am sorry to hear you sprained your ankle, I am not sure what I can tell you at the moment but if you book an appointment with me, I am sure we can get the recovery process started.”

“I can’t make a comment on that right now but if you need to book in with me, I can give you a much better evalua-tion of your injury and some definite advice on what you should be doing for it.”

“That sounds serious. It might be wise to go to the doctor to get that checked out first. If they give you the ok, then you can come see me next week.”

All are polite responses that show that the physiotherapist cares but can’t do much about it at the time they are approached.

Vignette Continued:

Eeson has started to use some standard phrases when he is approached outside of his work. Initially, he felt awkward with some of the conversations and worried that people felt he was directing them to the clinic for financial reasons only. However, he now feels quite comfortable letting people know why he can’t help them in the moment and directing potential clients to the clinic for an appropriate assessment or treatment.

The same concepts could be applied if a physiotherapist

was approached in an urban small community setting where people knew he was a physiotherapist, like after a slow-pitch game or at a community event.

Privacy Considerations

Being a member of a small community can also pose some privacy considerations that a physiotherapist may not have to worry about as a member of a larger community.

Running into clients or their family members outside of work:

Depending on the size of the community, this may be common or rare, but it does happen. Physiotherapists are encouraged to give the client the opportunity to either acknowledge the physiotherapist or not. For whatever reason, the client may not wish to say hello and it is best to respect that. On the other hand, if the client approaches the physiotherapist with questions or updates regarding their injury or condition, the public venue may not be the best place to engage in that type of discussion. There is an increased risk to a client’s privacy, with personal information being shared in a place where others may hear the details of the conversation.

As discussed previously there are issues with providing advice or guidance based on an interaction occurring outside of the practice setting, as well as the inability to document the conversation appropriately.

Physiotherapists who find themselves in this situation must be mindful of the risks of being overheard and the potential that the patient may not disclose all relevant information due to privacy considerations, nor would it be appropriate for the physiotherapist to ask more sensitive questions as part of such an interaction. As in the previous discussion about people approaching a physiotherapist in the street, the same types of responses are recommended, and the physiotherapist should redirect the client back to the practice site to continue the conversation.

Similarly, there is an increased risk that a physiotherapist who is a member of a small community may encounter a client’s friend or family member and an increased likelihood that the physiotherapist may be asked about the client’s condition, improvements, etc. A physiotherapist cannot share any client information with family or friends without the consent of the client and will need to be prepared to reinforce this with the friend or family member. Most people will be respectful of that decision and for following one’s professional responsibilities of confidentiality. Maintaining client confidentiality in one instance will set the tone for how a physiotherapist may manage their therapeutic relationships within the community. It may also help grow trust within the community that the physiotherapist respects all their clients’ privacy and confidentiality.

Small Community & Small Practice Site

Physiotherapists practicing in a small community may have clients who know each other with overlapping appointments in the practice setting. Curtained-off treatment areas are not soundproof and on occasion a physiotherapist may find they get “curtain neighbours” that know each other, or clients may be sitting and chatting together in the waiting room. It is up to the client if they choose to disclose details of their injury or care to their friend or acquaintance, but the

physiotherapist should be considerate of their privacy. A physiotherapist should pay attention to and follow client cues about feelings of privacy in the treatment space and tread cautiously towards topics that may be more sensitive in nature. The physiotherapist can offer them a more private space if they recognize the situation or anticipate the need to discuss details the client may consider sensitive and may not want to have known.

Making Friends

Vignette:

Maria recently moved to a small town and is working at the local hospital. Since Maria is new to town, she is trying to get out in the community to make friends. Maria is aware of the potential risk to the therapeutic relationship, so they avoid discussing the fact that they are looking for ways to make friends in their new community while at work. However, one of Maria’s clients invites them to come play on their slow-pitch team this weekend. Should Maria accept the invitation?

Considerations that may impact the therapeutic relationship:

Conflict of Interest – the physiotherapist must avoid any real or perceived conflict of interest. In the scenario, Maria would have to consider the potential for this to undermine their objectivity regarding the client and result in a conflict of interest. Would going to play softball for the weekend with this client and their friend group result in a real, perceived, or potential conflict of interest? Like gift giving, the risks related to friendships with clients and former clients exist on a continuum. Depending on the situation and people involved there may be a conflict of interest that the physiotherapist must avoid or manage.

Power Imbalance – anytime a physiotherapist is engaged in a therapeutic relationship they will be in a position of power. Is this position of power affecting decisions that are being made by or about the client? Would a friendship relationship affect the decisions or recommendations the physiotherapist makes as they try to develop or maintain the friendship? This is a much bigger issue if the client is a WCB or MVC client where the physiotherapist can have a significant impact on their client’s claim. Consider the extent of the power imbalance and if this could be compromising the physiotherapist’s judgement.

Potential Fallout – what would happen if a physiotherapist met and engaged in a platonic friendship outside of the therapeutic relationship and things did not go well? What are the potential consequences if the client were unhappy with the outcomes of their physiotherapy care? What would the potential fallout be for the physiotherapist and the client? How likely is it that the desire to avoid social repercussions may affect the physiotherapist’s professional judgment and behaviours?

Vignette Continued:

Because of the nature of their relationship with the client and concerns about the potential consequences if the personal relationship does not go well, Maria opts to defer joining the slow-pitch team until after the client has been discharged from physiotherapy. Maria knows that context matters in her decision-making and that what she chooses to do with the slow-pitch team may differ from what she does with future comparable invitations from clients and former clients.

- Ridling DA, Lewis-Newby M, Lindsey D. Chapter 9 -Family-Centered Care in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Editor(s): Fuhrman BP, Zimmerman JJ. Pediatric Critical Care (Fourth Edition), Mosby, 2011;92-101. https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-0-323-07307-3.10009-6.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta Code of Ethical Conduct. https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/regulatory-expectations/code-of-ethics/

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta Standards of Practice. https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/regulatory-expectations/standards-of-practice/

- Miciak, M., Mayan, M., Brown, C. et al. The necessary conditions of engagement for the therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: an interpretive description study. Arch Physiother 8, 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-018- 0044-1

- Wright KM. The therapeutic relationship in nursing theory and practice, Mental Health Practice. (2021) DOI:10.7748/mhp.2021.e1561.

- McCabe E, Miciak M, Roduta Roberts M, Sun H, Gross DP. Measuring therapeutic relationship in physiotherapy: conceptual foundations, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2022;38(13):2339-2351, DOI: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1987604

- Hush JM, Cameron K, Mackey M. Client satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy care: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2011;91:25–36. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20100061.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML. The influence of the therapist-client relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1099–1110. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20090245.

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and clients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2013;93:470–478. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20120137.

- Kleiner MJ, Kinsella EA, Miciak M, Teachman G, McCabe E, Walton DM. An integrative review of the qualities of a ‘good’ physiotherapist. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2023;39(1);89-116, DOI:10.1080/09593985.2021.1999354

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and Assessing Professional Competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2002;287:226–235.

- College of Physical Therapists of British Columbia: Professional Boundaries in a Therapeutic Relationship https://cptbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CPTBC-wheres-the-line-2019.pdf

- College of Nurses of Ontario. Professional vs. Social Relationships. https://www.cno.org/en/learn-about-standards-guidelines/educational-tools/ask-practice/social-versus-professional-relationships/

- Pugh D. A fine line: The role of personal and professional vulnerability in allegations of unprofessional conduct. Journal of Nursing Law 2011; 14(1):21-31.

- British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives. Warning signs: do you know when you’re crossing a boundary? https://www.bccnm.ca/RPN/learning/boundaries/Pages/boundary_crossing_violation.aspx

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta: https://www.cpta. ab.ca/news-and-updates/webinars/professionalism-in-the-era-of-social-media/

- Australian Physiotherapy Association. When does an examination turn inappropriate. (2023) https://australian.physio/inmotion/when-does-examination-turn-inappropriate