Over the course of a career, physiotherapists will inevitably encounter challenging situations. This is part of providing care to a diverse public and interacting with individuals whose different lived experiences and values can increase the likelihood of misunderstandings or conflicts. This guide is intended to provide assistance to physiotherapists and serve as a road map through these challenging situations.

Managing Challenging Situations Guide PDFPhysiotherapists work with people; they often work with people who are hurt or injured and facing significant life challenges. It is therefore reasonable to expect that physiotherapists will come across several challenging situations during their careers.

Challenging situations can arise in a multitude of ways and can affect physiotherapists in any of their roles, including clinicians, supervisors, managers, or business owners. A challenging situation can be any situation that gives a physiotherapist pause or puts them in a position of uncertainty or conflict. More specifically to physiotherapy practice, it would be any situation that affects their ability to deliver quality, safe, and effective care to their client.

These situations can occur not just with patients, but with patient’s families or peers. They can also occur in supervisory relationships.

This guide is intended to help physiotherapists navigate these situations and provide strategies for planning how they will respond to the challenging situations they encounter. The guide uses a “principles-based approach” as each situation will come with its own nuances and context which the physiotherapist will have to consider before coming to a decision on how to proceed.

As regulated health professionals in the province of Alberta, physiotherapists must adhere to the legislation that applies to their practice, the Code of Ethical Conduct¹ that identifies the professional values and ethical principles relevant to the profession, and the Standards of Practice² that establish the minimum performance expectations that physiotherapists practice by.

This guide will:

- Review physiotherapists' professional responsibilities.

- Discuss foundational concepts relevant to conflict and challenging situations.

- Provide a framework for working through and addressing challenging situations.

- Highlight other resources available to physiotherapists.

How to use this guide:

A proactive approach to managing conflict is preferred. This guide will provide you with information on why conflicts arise, components of effective relationships, and outlines a few communication and conflict management techniques.

If you are currently in a challenging situation, go to "A Step-by-Step Guide to Managing the Challenging Situation."

Code of Ethical Conduct

The Code of Ethical Conduct¹ outlines the foundational ethical principles of:

- Respect for patient autonomy

- Beneficence

- Least harm

- Justice

Physiotherapists can use these ethical principles to guide them when they find themselves in a conflict or challenging situation. When we look closer at the expectations for physiotherapists within the Code of Ethical Conduct¹, the main messages are to:

- Demonstrate sensitivity towards the person and consider their unique rights, needs, beliefs, values, culture, goals, and the context of the situation, and to conduct themselves with integrity and professionalism.

- Communicate openly, honestly, and respectfully with each person and work with them to achieve their goals whether as a patient, a patient’s support person, or a colleague.

- Maintain respect and professional boundaries with those they interact with in their role as physiotherapist.

- Commit to taking responsibility and care for their own physical and mental health and recognize when their ability to provide competent care is compromised.

Standards of Practice

The Standards of Practice2 refer to the expected level of performance for professional physiotherapy practice that leads to safe, ethical, and effective physiotherapy service.

There are several Standards of Practice2 that relate to how a physiotherapist would manage a challenging situation. Highlights of the Standards of Practice2 and the expected performance that relate to managing challenging situations are below.

Boundary Violations: the physiotherapist acts with integrity and maintains appropriate professional boundaries with clients, colleagues, students, and others.

Communication: the physiotherapist communicates clearly, effectively, professionally, and in a timely manner to understand and be understood by the client which supports and promotes quality services.

Duty of Care: the physiotherapist has a duty of care to their clients and an obligation to provide for continuity of care whenever a therapeutic relationship with a client has been established.

Health Equity and Anti-Discrimination: all individuals inhabit more than one social location and possess a unique combination of identities and individual characteristics. This can include but is not limited to characteristics such as physical appearance, body size and shape, use of mobility aids, and identity factors such as religion, ethnicity, sexual identity, gender identity, or social group.

The physiotherapist demonstrates respect and seeks to provide care that is safe, equitable, and inclusive of the client’s identity, culture, and individual characteristics.

Indigenous Cultural Safety and Humility: the physiotherapist demonstrates cultural humility and strives to provide culturally safe physiotherapy services when working with Indigenous clients.

Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct: the physiotherapist abstains from conduct, behaviour, or remarks directed towards a patient that constitute sexual abuse or sexual misconduct. The definition of sexual misconduct includes remarks of a sexual nature by a physiotherapist towards a patient that the physiotherapist knows or ought to know will or would cause offence or humiliation to the patient or adversely affect the patient’s health or well-being.

The Code of Ethical Conduct and the Standards of Practice provide guidance and must be upheld by physiotherapists as they work through the framework for managing a challenging situation.

This section is intended to provide a realistic process that a physiotherapist can use when dealing with a challenging situation.

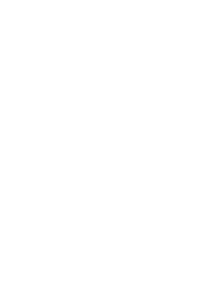

Self-awareness: physiotherapists should be aware of their own preferences and behaviours when it comes to dealing with challenging situations.

Planning and implementation: outline the steps for how one would deal with the situation as well as strategies for de-escalation if the conversation is not going according to plan.

Reflection: is an essential step after the situation has occurred. The physiotherapist reviews their plan, how it went, what they could have done differently, and what they may do next time.

Challenging situations provide an opportunity for growth and improvement and hopefully, this section will provide a framework by which the physiotherapist can continue to improve their ability to manage challenging situations.

Self-evaluation is a critical step in managing a challenging situation. Identifying and understanding how someone usually deals with conflict or challenging situations can create self-awareness and allow them to recognize their own tendencies. Then, they can identify a discrepancy between how they usually deal with a situation and how they can better deal with the situation to achieve the best outcome.3

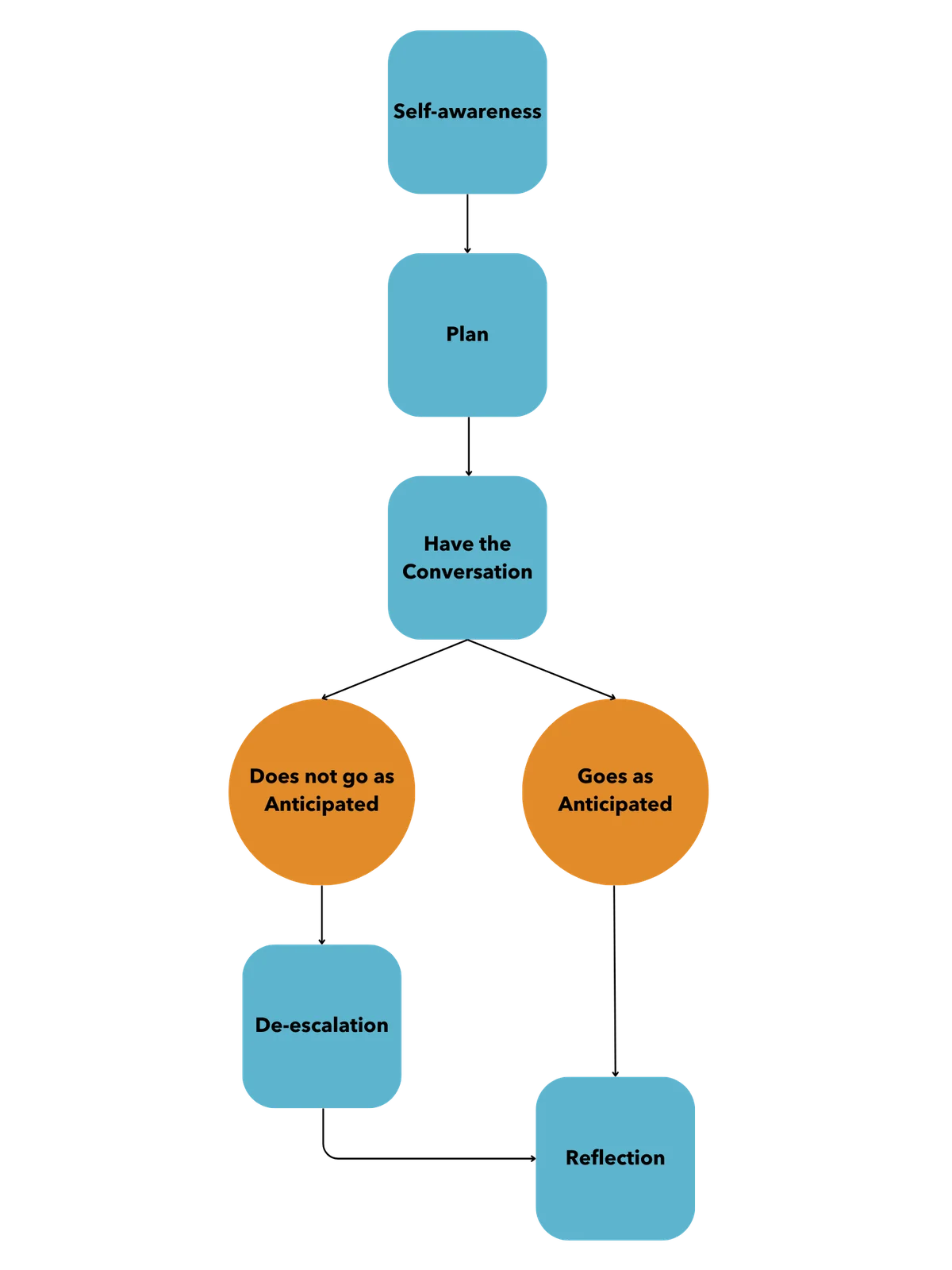

One of the most widely used models for conflict resolution is the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Model. In this model, there are 5 ways in which people respond to conflict and can be viewed as a blending of Cooperative or Uncooperative and Assertive or Unassertive.3 The conflict types describe the behaviours people may be predisposed to when dealing with conflict.

Any of these behaviours could be applied to a situation but it’s important to recognize the positives and negatives of each behaviour and weigh which one might best be applied to a situation. A physiotherapist should keep in mind their personal preferences as to how they are most comfortable reacting.

- The Avoider: avoiders do not deal with conflict and do their best to avoid it. This behaviour is viewed as both unassertive and uncooperative as they do not engage with the other party to deal with the situation.

- The Competitor: a competitor’s thoughts on dealing with conflict come down to winning or losing by attempting to dominate the other person, which is an assertive behaviour. This is also uncooperative as they do not wish to listen to the other person.

- The Accommodator: is the opposite of the competitor as they are unassertive and cooperative. They attempt to satisfy the other person at the sacrifice of their own needs or opinions.

- The Compromiser: those who tend to compromise seek the intermediate of both assertiveness and cooperation. They seek to find a mutually acceptable solution that ends up partially satisfying both people involved.

- The Collaborator: collaboration is both assertive and cooperative but requires both people involved in the situation to actively work to create a solution that fully satisfies both people involved. Collaboration requires both parties to engage in discussions to explore possible solutions. Generally, this may provide the most meaningful outcomes when managing conflict but is the most time-consuming.3

Self-awareness can be helpful, however, incorporating that knowledge and putting it into practice can be challenging. These non-technical skills take time to practice and refine and even when someone may be good at it, they may still find themselves in a challenging situation. Below are steps that a physiotherapist can take to manage the challenging situation they face.

- Plan in Advance: an issue has been identified, or the physiotherapist is working preventively.

- Have the conversation planned in advance. The physiotherapist plans what they will say, the patient’s possible replies, and how the conversation can be brought to a close.

- Plan for the various potential responses and outcomes to the conversation. How might the client react? What might the client say in response to what they are being told? Consider different possible scenarios for the conversation.

- Discuss the plan with someone trustworthy or call the College’s Practice Advisor to discuss the situation.

- Have an exit strategy. Plan different ways to end the conversation or the interaction. If there are safety concerns, the physiotherapist is advised to have a colleague nearby who is aware of what is occurring and able to intervene and assist if there are concerns.

- Depending on the nature and severity of those concerns, having a colleague or manager present in the room for the conversation might be required.

- Set Boundaries: a physiotherapist should be able to identify what they are comfortable with and what they are uncomfortable with.

- Respect should be shown for someone’s personal space. If needed, let the other person know if they are impinging upon that personal space.

- Lay out the intent of the conversation and how best to proceed.

- Make the boundaries clear, simple, reasonable, enforceable, and consistent.

- Pay Attention:

- Look for non-verbal or paraverbal cues that can indicate if the situation is escalating out of control.

- A physiotherapist should be conscientious of their own non-verbal and paraverbal cues to display that they are listening attentively and empathetically.

- If the situation has escalated past the point the physiotherapist is comfortable with, they should try to keep the situation calm and ensure the safety of both themselves and the other person when possible.

- Continue Communicating:

- Allow the opportunity to voice concerns.

- Explain the challenge and try to find common ground.

- Remain calm; it will help the other person stay calm as well.

- Highlight solutions. Try to create bridges of communication and trust.

- Give rational answers to information-seeking questions.

- End the Conversation:

- If the conversation has failed, have an exit strategy to bring the conversation to a close.

- The physiotherapist should allow themselves or the other person the ability to remove themselves from the situation at any moment if they are no longer able to continue in a reasonable manner.

- Bring the conversation to a close and summarize the key points and any actionable items.

Unfortunately, conversations to address challenging situations do not always have the intended outcome. It is good to identify when a physiotherapist would need to de-escalate a situation and how to go about doing so. The use of Hallet’s SHARE elements of verbal communication can be helpful in these situations.4

- Simplicity: simple language with short sentences is better for those in a high-tension situation who may have challenges understanding complex information. It is okay to repeat messages to ensure the person the physiotherapist is communicating with understands them.

- Honesty: the message a physiotherapist is conveying should be honest, and they should not make false promises that they may be unable to keep. The physiotherapist should be honest about how that person is making them feel and needs to honestly consider how they may be making the other person feel. Often when people are getting agitated, they do not intend to invoke fear or to intimidate someone. Being honest about one’s feelings can limit the perception of intimidation.

- Authenticity: if the physiotherapist is acting authentically, they are allowing better engagement and building trust in the relationship. The person they are interacting with will pick up on their non-verbal and paraverbal cues if the physiotherapist is not acting authentically.

- Rapport: understanding one another and being empathetic to the other person’s needs or ideas will help them regain control. Building rapport requires a shared understanding and the ability to see things from their side.

- Empathy: part of building rapport comes from being empathetic. The physiotherapist does not have to agree with someone in order to be empathetic with what someone is feeling. A higher perceived level of empathy also leads to establishing rapport with that person.

De-escalation training may be something a physiotherapist, clinic owner, or someone in a lead or management position may wish to consider for both themselves and their staff.

Occasionally, challenging situations may continue on, even after there has been a meaningful discussion with the other parties involved. There may be a period of continued management where the therapeutic relationship is restored but requires continued focused work to maintain it.

After a situation has occurred, whether there is closure or not, reflection is an important part of managing a challenging situation.

Reflecting upon the potential biases a physiotherapist may bring into the situation and potential contributing factors such as feelings of being stressed, overwhelmed, etc. can assist in identifying potential reasons that created the situation to begin with. Proactively dealing with one’s own assumptions, feelings, and biases can allow a healthier approach to those around them. Reflecting on and clarifying that their patient, peer, or someone they are in a supervisory relationship with has their own feelings, biases, and lived experiences can increase a physiotherapist’s empathy towards them and will create a healthier relationship.

Whether the challenging situation was dealt with well or poorly still creates a learning opportunity and a chance to grow as a physiotherapist and as a person. Having someone identify how they dealt with the challenging situation and taking time to consider how they could have improved upon it is necessary for growth and can be viewed as part of a physiotherapist’s ethical obligations to the patient and those around them in the workplace.

It is important to seek help from mentors, supervisors, or trusted peers to help make positive changes in the event a physiotherapist experiences challenging situations. Identifying and dealing with their own health and well-being is also extremely important and part of the College’s Code of Ethical Conduct.1 As a physiotherapist, it is not uncommon to have feelings of stress, anxiety, frustration, or helplessness. Physiotherapists may need to ask themselves, "Are there mental health considerations that I may need help to manage?"

Challenging situations will arise. It is as inevitable as death and taxes. But why is it so inevitable that a physiotherapist would have to deal with a challenging situation? In this section, we will dissect what causes challenging situations and provide suggestions for things to consider and actions to take to manage and prevent challenging situations proactively in the future.

WHAT ARE THE POTENTIAL NEGATIVE OUTCOMES OF CHALLENGING SITUATIONS?

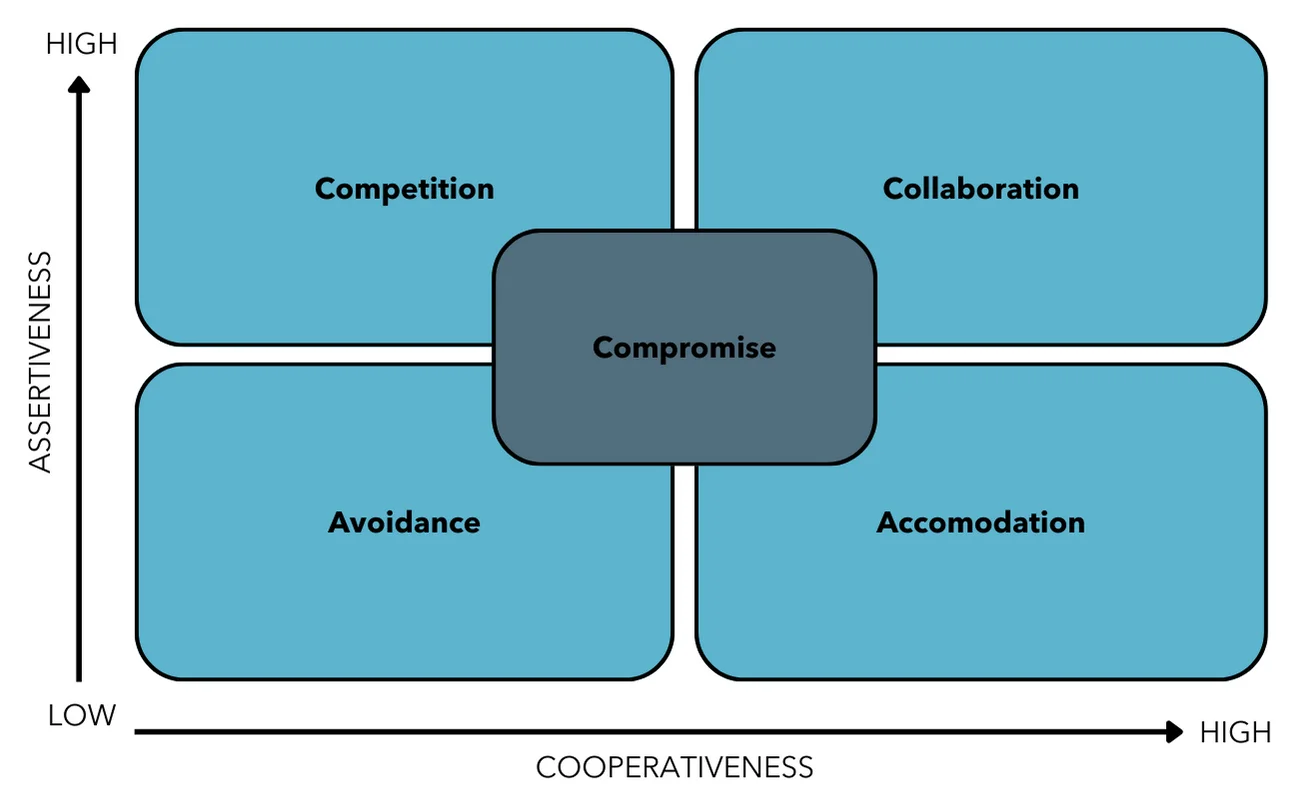

Patients want to have a positive experience with their physiotherapist and physiotherapists want to provide an environment where that can occur. However, when challenging situations or negative therapeutic relationships exist, potentially both the patient and the physiotherapist will experience stress, frustration, anger, helplessness, or other negative emotions. These processes can be considered in a cascade as it is most often one experience or emotion flowing from another and the sum of these experiences and emotions spill over into unintended outcomes.

Management of challenging situations and conflict creates significant costs to the patient, the system, and the physiotherapist financially, physically, and psychologically. Financially, the costs associated come from reduced productivity and interrupted patient care. Those patients who exhibited challenging behaviours were particularly vulnerable to interrupted patient care and reduced productivity.5

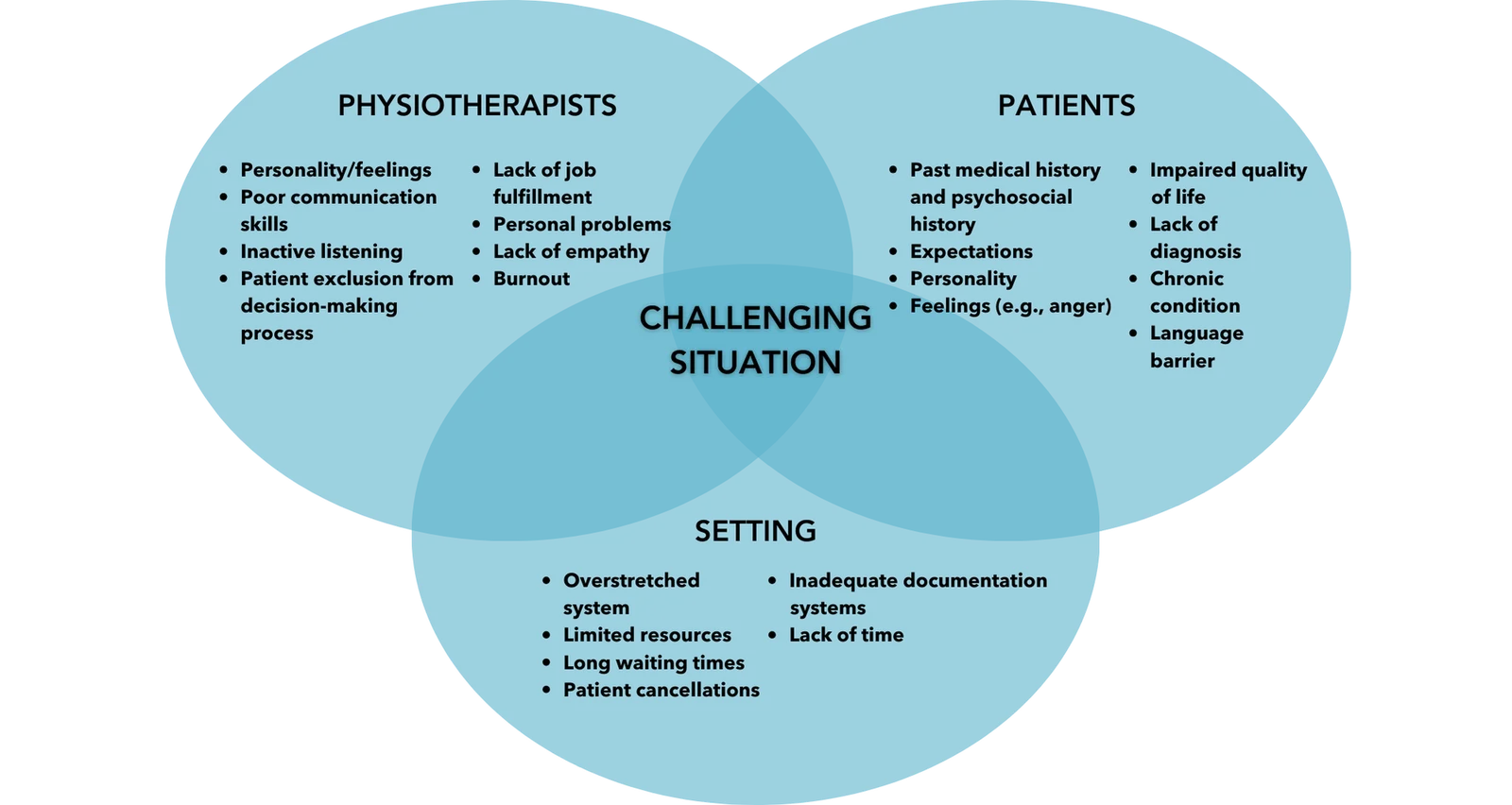

First, let’s look at the elements or factors that contribute to a challenging situation so the physiotherapist may be able to prevent a situation from reaching the point where it negatively affects patient care. This guide breaks these down into the 3 elements of The Physiotherapist, The Patient, and The Setting.

Predisposing Factors

The Physiotherapist

As a regulated health professional, the expectation is that a physiotherapist must act professionally in all interactions. This can be challenging in itself as things both inside and outside of work can lead to feelings of being overwhelmed and stressed which can lead to a challenging situation.4,5

- Stress: physiotherapists are not robots, and no one expects them to be impervious to the things that normally affect people. Personal issues inside or outside of the workplace are challenging to ignore while at work. The Code of Ethical Conduct1 refers to physiotherapists being responsible for their own health and well-being. Reflecting on and adopting healthy coping strategies can reduce how much of this they carry with them in their day-to-day work.

- Burnout: burnout and stress are related, but burnout often presents as occupational exhaustion, depersonalization, and a lack of fulfilment.5 A physiotherapist experiencing occupational exhaustion and depersonalization may have difficulty establishing effective therapeutic relationships with patients. Also, the issues that contribute to burnout, like staff shortages, can potentially create challenging situations on their own.

- Workplace morale: this can be affected by system issues as mentioned above, or it can be due to poor team chemistry, poor leadership, or workplace bullying. How likely is it that a physiotherapist would have good collaboration with another team member who is bullying them in the workplace? Having poor workplace morale can directly influence patient care and can also create precipitating factors to challenging situations because it not only affects the patient but can affect the other team members.

The Patient

Patients may be stressed emotionally and/or financially. They may also be in pain with limited coping strategies.

Building a positive therapeutic relationship with a patient is important to the overall care and success of treatment.

However, patient factors that are unrelated to the therapeutic relationship can pose inherent challenges to successfully developing that relationship.5-7

- Stress: this can come from many different areas of their life; it could be work, home, finances, etc. Stress can create many different negative effects and can harm the development and maintenance of a positive therapeutic relationship.

- Distress: patients come to physiotherapy because they are in pain or they cannot participate in their usual activities. This can create unusual reactions or heightened emotions in the patient.

- Frustration: this can be directed at the physiotherapist if the patient feels they aren’t being heard or at the system if the patient had to deal with long wait times to get in. Dealing with funders and financial stressors can also cause frustration.

- Past history of trauma: trauma-informed care has rightfully gained attention in the health care setting as a patient’s past history of trauma can lead them to respond in ways that are unexpected or can create barriers to a positive therapeutic relationship with the physiotherapist.3

Research from Hardavella et al. (2017) highlights how predisposing factors related to the patient, physiotherapist, or setting can all contribute to the development of challenging situations.

The College of Physiotherapists of Alberta recognizes that the traits listed in Figure 4 were adapted from research. However, while the factors identified may reflect realities of practice in some settings, many of the physiotherapist factors in particular are inconsistent with the expectations established in the Standards of Practice2. For example, the Standards of Practice2 and Code of Ethical Conduct1 clearly identify the importance of active listening, engaging the patient in decision-making, and demonstrating empathy towards the patient.

The College also acknowledges that the findings from this research are reflective of practice realities in some settings and are also evident in past professional conduct cases in Alberta and nationally.

The Setting

The setting that a physiotherapist may work in, whether public or private can lead to its own challenges.5 It is important to identify areas in which the physiotherapist or the practice site is struggling. Some potential areas of friction that can be monitored and addressed include:

- Time: patient volumes and booking practices can vary depending on the setting. The control a physiotherapist has over their schedule can also vary. Whether in private or public practice, patient volumes and how clients get booked can directly affect the time a physiotherapist may have to communicate with them effectively, or for them to feel that quality care is being delivered.

- Waitlists: clients can become frustrated when they have to wait days or weeks to access care if they are in pain or experiencing loss of their ability to function or engage in activities of daily living. Scenarios where a patient has been waiting on an MRI or surgical list for months is not within the physiotherapist’s control, but this can lead to a poor start of care as the patient may come to their first appointment frustrated and upset.

- System issues: system issues refers to the way a practice setting is managed or set up. This can be how administrative tasks are done, how management views physiotherapy services, or how the physical space creates barriers to quality care. The patient and the physiotherapist do not always have control over these aspects, but they can create friction within the team and within the therapeutic relationship.

Contributing Factors

Values

Differences commonly exist between individuals and much of the time these differences do not lead to challenging situations.5 Some of the common differences that can create a challenging situation are listed below.

- Differences of culture and worldview: cultural differences can become an issue between people who are members of different ethnicities and national origins. The role of the physiotherapist is to recognize their own potential biases and culture and seek to understand how the client’s identity and culture may affect their physiotherapy experience.

There can also be differences between the physiotherapist and the patient in

their view of the world including an individual’s values, beliefs, and

perspectives on politics, religion, public affairs, and current events.

The physiotherapist should incorporate an awareness of their culture,

worldview and biases, and respect for their client’s culture and worldview into

all aspects of the therapeutic relationship. Physiotherapists should recognize

potential contentious topics to avoid within the clinical practice setting and be

prepared to manage contentious discussion topics if they arise.

Positionality refers to where one is located in relation to their various social identities (gender, race, class, ethnicity, ability, geographical location, etc.); the combination of these identities and their intersections shape how we understand and engage with the world, including our knowledges and perspectives.

- Mismatched expectations: the patient’s expectations should be established and confirmed during the assessment and throughout the therapeutic relationship. The physiotherapist should assist the patient in identifying goals that are important to the patient and encouraging the patient to be as involved in the development of their care plan as the patient wishes to be. The physiotherapist may expect certain levels of commitment and participation from the patient. However, the physiotherapist shouldn’t assume the patient has the same values and priorities or capacity to participate.

Power

Power imbalances are common in therapeutic settings. Often the power lies with the physiotherapist as they have specific knowledge and influence over many different aspects of the therapeutic relationship. The physiotherapist provides diagnosis, treatment plans, and recommendations regarding the patient and their injury or condition. The physiotherapist is also often in a position of power in relation to those they supervise and in relation to those they may employ.

Power imbalances are not uniform and are influenced by the individuals’ positionality and what each person involved brings to the relationship.

Power imbalances of any kind can lead directly to challenging situations if the person in a position of power uses that power in a potentially harmful manner. If they use that power imbalance to exert their will onto another person or if they don’t wish to share their power, then this can have negative effects on the other person involved in the therapeutic relationship. A physiotherapist must consider their position of power when faced with challenging situations so that they can take the time to view the situation from the other person’s perspective.

Communication

Communication is one of the most common denominators for challenging therapeutic relationships, complaints, and poor therapeutic outcomes. Communication flows between the patient and the physiotherapist and although both share responsibility for effective communication, the physiotherapist is ultimately held responsible due to their professional role in the relationship.

- The physiotherapist can create or prevent challenging situations with their listening skills, choice of language, and use of non-verbal cues. A patient’s frustration can build when there is no clear direction coming from the physiotherapist or if the physiotherapist consistently uses ambiguous language.6

- The patient or other person involved in the conversation also plays an important role in effective communication. Patients who feel that the physiotherapist is not actively listening to them, not providing them with an opportunity to tell their story, or limiting their power in decision-making by being dismissive of their values or perspectives, can create feelings of frustration. The probability of a negative therapeutic relationship (and potentially a challenging situation) will increase if the patient's symptoms worsen, if the patient feels the physiotherapist has made an incorrect diagnosis, or if the patient feels their treatment plan is not working.

- Language barriers – communication is a key component to building a positive therapeutic relationship as well as a way to deal with a challenging situation. If the physiotherapist is unable to effectively communicate with a patient verbally and non-verbally then this can lead to tension between the patient and the physiotherapist and also increases the likelihood of a negative therapeutic relationship.

What Contributes to Effective Communication?

Effective spoken communication is made up of 3 aspects6:

- Verbal: the actual spoken words. Did the physiotherapist use appropriate words to communicate with their client? Did they communicate their information in a way that the patient could understand?

- Paraverbal: this is the tone, tempo, and volume of what someone is saying. This is the way someone would say their words.

- Non-verbal: facial expressions and body language create visual communication cues.

The complete message the other person receives is a mix of each of these types of communication. Effective communication occurs when all 3 forms of communication are consistent. When the words spoken with a matching tone do not match the body language, incorrect or confusing messaging exists and creates the opportunity for conflict to arise.6

Effective communication also requires that the physiotherapist take the time to actively listen to the person they are communicating with. Active listening requires the listener to be attentive to what the speaker is saying and repeating back to the speaker what has been heard to confirm that the listener has correctly understood the speaker. Failure to do so can also lead to an increased risk of creating a challenging situation.

Silence can also be an effective component of communication. Silence provides time to gather one’s thoughts to create a clear message to the other person. Silence can also show respect as it implies the person is taking the time to consider their thoughts and words prior to responding.4

10 Elements of Active Listening:

• Face the speaker.

• Maintain eye contact.

• Show understanding by responding appropriately.

• Minimize external distractions.

• Minimize internal distractions.

• Focus on the person speaking and what they are saying.

• Avoid telling the person how you managed a similar situation.

• Demonstrate good manners, for example not interrupting the person.

• Ask clarifying questions.

• Keep an open mind.

Physiotherapists have professional obligations to provide a continuation of care to their patients. Care begins at the initial assessment and continues until discharge. Discharge can occur due to many different reasons but ideally, it is because the patient is recovered or is able to self-manage their condition moving forward. However, there are some instances where the patient is discharged due to an irreparable breakdown in the therapeutic relationship. The following section will review common scenarios that physiotherapists have encountered.

Patients That Cancel or No-Show More Often Than They Attend

A physiotherapist has a patient that they have been treating for several weeks. Today the patient has cancelled for the 9th time in the past 2 months leaving the physiotherapist with another gap in their busy schedule. The patient has been following the clinic policy of providing notice for cancellations, but the physiotherapist is getting the feeling that the patient is not invested in physiotherapy or following their plan of care. The physiotherapist is frustrated about the situation but unsure what they can do about it at this point.

Whether it’s the patient’s attendance or lack thereof, or the patient shows outward signs of not being invested in their plan of care or a general breakdown in a positive therapeutic relationship, it is challenging to deal with. In this specific case, the patient’s pattern of attendance would not typically be expected to be effective in addressing the patient’s needs and goals.

With this in mind, the physiotherapist could consider:

- Would the patient do better with a different approach to care or with a different physiotherapist?

- Is there an issue with the therapeutic relationship that is driving the patient’s behaviour?

- How do the frequent cancellations affect other patients who could have used that spot for treatment?

The College defines a therapeutic relationship as:

“The relationship that exists between a physiotherapist and a patient during the course of physiotherapy services. The relationship is based on trust, respect, and the expectation that the physiotherapist will establish and maintain the

relationship according to applicable legislation and regulatory requirements and will not harm or exploit the patient in any way.”

Implied in the definition is that both parties to the relationship trust and respect each other. However, in this scenario the physiotherapist has not been able to establish an effective therapeutic relationship and frustration begins to affect patient-provider interactions. The physiotherapist may feel the patient is being disrespectful of the physiotherapist’s time and effort and their need to treat other patients.

Trauma-informed care was mentioned previously in the section on predisposing factors to challenging situations and is applicable here as well. It is important for the physiotherapist to consider the patient's reasons for the cancellations and to recognize the role of past and present life experiences, which can create barriers to accessing and following through with care. There could be several reasons for the multiple cancellations including transportation barriers, family caregiving responsibilities such as inconsistent childcare, or work demands. The patient may or may not wish to disclose their personal matters affecting their attendance, but it is essential that the physiotherapist take the time to try and understand the patient’s perspective and what barriers may be affecting their ability to attend scheduled appointments.

Although there may be situations where the physiotherapist could be justified in ending the therapeutic relationship due to frequent cancellations or if the patient-provider relationship has deteriorated, the physiotherapist must discuss the situation with the patient prior to taking any action.

If the physiotherapist were to choose to discharge the patient, they would have a responsibility to explain their decision to the patient, including the reasons for the decision and to document the decision. The physiotherapist would also have a responsibility to advise the patient of other service options available to them.

Getting Asked Out by a Patient

A physiotherapist has been treating a patient for the past few weeks and they feel that the patient may be developing feelings for them outside of the therapeutic relationship. Looking back, the physiotherapist realizes that they missed some opportunities to be direct and clear about the nature of the relationship and there may have been some blurring of professional boundaries. At the end of the treatment session today the patient requests the physiotherapist’s number and asks if they want to get a coffee this weekend.

Legislative changes and updates to the Standards of Practice2 regarding sexual abuse and sexual misconduct prohibit any conduct, behaviour, or remarks directed towards a patient that constitute sexual abuse or sexual misconduct.

The physiotherapist must abstain from any sexual conduct with a patient for a minimum of 365 days from discharging a patient.

Dating a former patient is generally not a good idea, even after 365 days have passed.

Here are some key points to keep in mind if a physiotherapist is approached by a patient or is worried that boundaries are being blurred:

- It’s the physiotherapist’s job to establish professional boundaries that maintain the therapeutic relationship. In this situation, hopefully, the physiotherapist can politely decline the invitation and re-establish the professional boundaries expected in a therapeutic relationship. Failure to do so should result in transferring the patient to another provider.

- Even if the physiotherapist does transfer the patient to another provider, in the case where they wish to see the patient in a romantic relationship, transferring the patient to another physiotherapist does not make it acceptable to begin dating. Transferring the patient does not allow the physiotherapist to enter into a sexual relationship with the patient until 365 days have passed from the date of the last documented physiotherapy service provided.

- Due to the inherent imbalance in power found in a therapeutic relationship, even if the patient were to instigate a relationship with the physiotherapist or agree to pursue a romantic relationship, the patient’s “consent” to the relationship is not considered valid.

- The physiotherapist could decline the invitation by pointing to the Standards of Practice – Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct² and the fact that they could lose their license if they became romantically or sexually involved with a patient within one year (365 days) of providing physiotherapy services to them.

- Point out that the relationship between patient and physiotherapist is a professional one and that the physiotherapist cares about the health of the patient from a professional perspective. Remind the patient that this is not a personal relationship, and cannot be, given the previously mentioned power imbalance between the two parties and the rules of the College.

- Reflect upon the professional relationship that existed and identify if there were any behaviours that could have contributed to the situation. Often times accepting (or giving) gifts or interacting with patients outside of the clinical environment, whether in person or on social media, can lead to issues.

Abuse

Physiotherapists are not expected to put themselves in a position of harm when providing services. Abuse comes in many forms. It can be emotional, physical, verbal, or sexual in nature and can be perpetrated by a peer, someone with whom the physiotherapist has a supervisory relationship, or someone they have a therapeutic relationship.

The Abusive Patient

A physiotherapist works at a busy outpatient clinic. They have a patient who has disclosed in previous sessions that they have a short fuse but are trying to work on it. Several weeks go by and after a treatment session with the patient, the physiotherapist walks out into the hallway to find the patient raising their voice at the administrative staff because they can’t get him an appointment for next week. The physiotherapist approaches the patient to help resolve the situation, but the patient turns their anger on the physiotherapist and uses racist and derogatory language towards the physiotherapist. The clinic’s manager comes to try to help manage the situation and is eventually able to help the patient calm down and convince them to leave the clinic.

In the above scenario, there are several things to consider.

- What is in the best interest of the patient? Will the physiotherapist be able to provide effective, quality, and competent care, or will the incident alter the therapeutic relationship beyond repair?

- Is it reasonable for the physiotherapist to refuse care to the patient and on what grounds would they base that decision?

- Is it reasonable for an employer to keep their employees safe and support this patient in finding treatment elsewhere?

- Could it be reasonable to accommodate the patient if they apologize to the staff?

- Is there an ongoing risk to the staff by having the patient attend the clinic after their outburst?

The decision was made to discharge the patient from the facility due to concerns over the safety and well-being of the physiotherapist, staff, and other patients present in the clinic. The physiotherapist called the patient the next day to explain they were being discharged from the clinic due to their verbally abusive language and threatening behaviours that were unacceptable. The patient was directed to access care at the next nearest facility and provided with contact information so they could make an appointment.

The patient calls the clinic manager the next day to accuse the clinic of discrimination by not allowing them access to the clinic.

According to the Code of Ethical Conduct¹, physiotherapists must act in a respectful manner and must not refuse care to a client on the prohibited grounds of discrimination as specified in human rights legislation. In this scenario, the decision was based on concern for the safety and well-being of the physiotherapist and others in the practice setting. Physically, verbally, emotionally, or sexually abusive behaviours are not protected grounds. The physiotherapist has the right to decline to provide physiotherapy services to patients who are physically, verbally, emotionally, or sexually abusive.

Considerations Regarding the Alberta Human Rights Act and Conscientious Objection

The Alberta Human Rights Act9 is established to provide Albertans with protection of their human rights. The Act prohibits discrimination under “protected grounds.” The Alberta Human Rights Act identifies the following as prohibited grounds: race, religious beliefs, colour, gender, gender identity, gender expression, physical disability, mental disability, age, ancestry, place of origin, marital status, source of income, family status or sexual orientation. The Code of Ethical Conduct1 further specifies that physiotherapists act in a respectful manner and do not refuse care or treatment to any client on the grounds of social or health status.

Physiotherapists cannot discriminate against patients for any of these reasons regardless of their personal beliefs.

Health Status

In the situation where the patient discloses that they have a communicable disease, a physiotherapist cannot discriminate against them on the basis of their health status. The patient is entitled to safe, quality, and effective care. There may be limits to the health services offered if a treatment poses a risk to the service provider and others in the practice setting, however, any assessment of risk to the provider needs to be factually based and not grounded in assumptions or fear about the risk of spread of the disease. The physiotherapist must also con-sider the physical, technical, and administrative controls they can put in place to mitigate the risks identified.

Social Status

Another recurring scenario is that of being asked to treat a patient who is incarcerated or who has a prior criminal conviction. The conviction is not a reason for which a physiotherapist can decline to provide service to the patient as a past criminal conviction is a social status as identified in the Code of Ethical Conduct.1

Patients can expect that the physiotherapist and the facility would adopt physical, technical, and administrative controls to protect against identified risks in practice while still considering the patient’s needs and respectfully providing care that is safe, quality, and effective.

| Scenario | Challenge | Action |

|---|---|---|

The patient is intoxicated at their visit. The physiotherapist doesn’t treat the patient. The patient leaves and is driving while intoxicated. |

The patient is driving while impaired and this poses a safety risk to the patient and the public. |

The Traffic Safety Act¹⁰ does not require the physiotherapist to report the situation, however local authorities encourage reporting of impaired drivers and the physiotherapist has an ethical duty to act. The Personal Information Protection Act¹⁵ and the Health Information Act¹⁶ both have provisions that allow reporting. See Appendix A for more information. Contact the local police service by calling 911 (or other emergency response phone number). |

The patient has a history of previously controlled seizures but has recently been having seizures again. The physiotherapist is aware of the patient’s seizures and that the patient continues to drive their vehicle. |

The patient’s uncontrolled seizures and the risk that they will experience a seizure while driving pose a safety risk to the patient and the public. |

The Traffic Safety Act¹⁰ does not require the physiotherapist to report the situation, however, the physiotherapist has an ethical duty to act. The Personal Information Protection Act¹⁵ and the Health Information Act¹⁶ both have provisions that allow reporting. The Traffic Safety Act¹⁰ provides protection for a health professional who reports a person’s medical condition that may impair their ability to safely operate a motor vehicle. See Appendix A for more information. Contact the Government of Alberta; Driver Fitness and Monitoring.¹¹ |

The physiotherapist suspects that their patient, a dependent adult, is being mistreated by a caregiver. |

Vulnerable persons such as elders in care are at increased risk of abuse by caregivers.¹² |

The Protection of Persons in Care Act¹³ requires that health professionals report these situations. Contact the Protection of Persons in Care at 1-888-357-9339 or the local police service. |

The physiotherapist suspects that their patient, a minor, is being mistreated by their parents. |

Children and youth can be subjected to abuse, neglect, or other circumstances that require intervention.¹⁴ |

The Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act¹⁴ requires that anyone who has reasonable and probable grounds to believe that a child is in need of intervention shall contact the Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-387-5437 or the local police service. |

The patient reports that they are experiencing suicidal thoughts. The patient asks the physiotherapist not to tell anyone. |

The physiotherapist is concerned that the patient may harm themselves but is concerned about breaching the patient’s privacy. |

Neither the Personal Information Protection Act¹⁵ nor the Health Information Act¹⁶ require that the physiotherapist report the situation, but both Acts have provisions that allow reporting. See Appendix A for more information on what to do. |

The patient expresses their intent to harm another individual. |

The physiotherapist has concerns that another individual may be harmed. |

Privacy laws involved could be the Personal Information Protection Act¹⁵ or Health Information Act¹⁶ depending on the work environment. Neither include a positive duty to report but a physiotherapist may feel they have an ethical duty to act. See Appendix A for more information on what to do. |

The patient reports that they were injured at work but requests that the physiotherapist not report the injury to WCB. |

There are concerns from the worker about potential repercussions for filing a WCB claim. The Physiotherapist might be concerned about the therapeutic relationship if they go against the patient's wishes. |

According to the Workers’ Compensation Act¹⁷, physiotherapists must forward a report to the Workers’ Compensation Board within two days of the patient visit. |

In cases where legislation does not require a physiotherapist to report concerns to authorities (sometimes referred to as a positive duty to report), there may still be an ethical or moral imperative that leads the physiotherapist to share private information with other parties.

When there is not a positive duty to report, the physiotherapist must use their judgment to determine whether to report their concerns. In this situation, a physiotherapist needs to balance the potential consequences of not reporting the situation against the serious nature of breaching a patient’s privacy.

In these circumstances, the test for determining the need to report is as follows:

- The physiotherapist perceives that there is a clear risk of harm to the patient or any other clearly identifiable individual.

- The danger poses a risk of serious bodily harm or death.

- The danger is imminent (i.e., “a sense of urgency must be created by the threat of danger”).15,16

While the relevant legislation indicates that the danger must be imminent, this does not mean that the action must be occurring immediately. “The risk could be a future risk but must be serious enough that a reasonable person would believe that the harm would be carried out.”15

When all three requirements are met, legislation allows a breach of privacy without patient consent for the purpose of alerting the appropriate persons. Depending on the situation, this could be local police or RCMP, family members, the patient’s physician, or their mental health provider.

Expressing Intent to Harm a 3rd Party

If an individual is expressing the intent to harm a third party, the physiotherapist must use their judgment to determine whether to report this information and to whom. The same three requirements listed above are applied to determine if disclosure without consent is acceptable.

Regardless of the actions they take, the physiotherapist must endeavor to maintain a therapeutic relationship with the patient by offering support and acting in the patient’s best interest in keeping with the expectations in the Standards of Practice² and the Code of Ethical Conduct.1

Patients with Mental Health Concerns

Physiotherapists often treat patients who are facing significant illness or injury, ongoing pain, or significant changes to their personal and work lives. Due to these factors, patients can experience mental health concerns such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts that physiotherapists should be aware of.

A physiotherapist has been treating a 45-year-old for chronic back pain. The patient had disclosed using anti-depressants for the past 3 years and is frustrated with their lack of an active lifestyle due to their back pain. The patient has been an active participant in their physical recovery but has noticed very slow improvements. They are especially frustrated in treatment today and disclose they have been feeling more depressed than usual.

Even though physiotherapists do not treat any mental health conditions, they often find themselves working with patients who disclose this information, so what should a physiotherapist do in this situation?

- Be clear and direct and ask them about how they are feeling. It is important for a physiotherapist to establish that they are a safe person to talk to.

- Physiotherapists are not mental health therapists or psychologists, so focus on how they are feeling and provide support via resources or referrals to someone who is equipped to help.

- If some of the feelings the patient has are related to their ongoing health concern and how it relates to their current physical status and chronic pain, try to instill some hope that with the right care, they may see improvements (if it is relevant and applicable to the patient’s situation).

- Ask if they have talked to anyone else about these feelings. They may have already talked to a loved one, their doctor, or therapist. Knowing that others with the right knowledge and skill set to help them are involved will help a physiotherapist decide what their next steps might be.

If a physiotherapist has concerns about the patient's safety and well-being, they would use the same three criteria to determine whether or not to breach the patient's privacy and disclose the situation to other parties. If the physiotherapist decides to breach the patient's privacy, they would then need to use their professional judgment to decide the best individual or group to contact about the situation.

A physiotherapist works in a hospital setting and has recently taken over a caseload from a previous therapist. One of their patients tells the physiotherapist during treatment that they are so happy to have a different physiotherapist. When the physiotherapist asks why, the patient tells them that the previous physiotherapist made several sexually suggestive comments during their sessions that made the patient really uncomfortable. The patient didn’t really know what to do and didn’t want to say anything as they were getting better. When the physiotherapist tells them that this behaviour was wrong, the patient is adamant they don’t want to make a fuss and don’t want to file a complaint.

The physiotherapist has a challenging situation to manage. They are receiving information from a patient that ties into the Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct Standard of Practice.2 This standard establishes the requirement that the physiotherapist report all instances where the physiotherapist has reasonable grounds to believe that the conduct of another physiotherapist constitutes sexual abuse or sexual misconduct.

The requirement set out in the standard is not that a physiotherapist must have proof of such a situation, but that they have “reasonable grounds to believe” that the conduct constitutes sexual abuse or sexual misconduct. The physiotherapist is required to report the incident to the College and inform the patient of that obligation. The patient has a right to not be a part of the process, but the physiotherapist must have the incident, their actions, and the disclosure to the patient documented in the patient’s client record.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Code of Ethical Conduct. https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/regulatory-expectations/code-of-ethics/

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Standards of Practice. https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/regulatory-expectations/standards-of-practice/

- Dotun Ogunyemi, MD; Susie Fong, BA; Geoff Elmore, MD; Devra Korwin, MA; Ricardo Azziz, MD The Associations Between Residents’ Behavior and the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict MODE Instrument. J Grad Med Educ (2010) 2 (1): 118–125. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-09-00048.1

- Hallett N. Preventing and managing challenging behaviour. Nursing Standard. 2018;32(26):51-63. doi:10.7748/ns.2018.e10969

- Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, Saad N, Niculescu A, Powell P. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor-patient interactions. Breathe (Sheff). 2017 Jun;13(2):129-135. doi: 10.1183/20734735.006616. PMID: 28620434; PMCID: PMC5467659.

- Boyd C, Dare J (2014) Student Survival Skills: Communication Skills for Nurses. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester

- Karjalainen K, Juntunen J, Kuivila H-M, Tuomikoski A- M, Kääriäinen M, Mikkonen K. Healthcare educators’ experiences of challenging situations with their students during clinical practice: A qualitative study. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research. 2022;42(1):51-58. doi:10.1177/2057158521995432

- Queen’s University Centre for Teaching and Learning. Positionality Statement. (2023) Available at https://www. queensu.ca/ctl/resources/equity-diversity-inclusivity/positionality-statement#:~:text=Positionality%20 refers%20to%20where%20one,including%20our%20 knowledges%2C%20perspectives%2C%20 and Accessed on December 13, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Alberta Human Rights Act. Alberta King’s Printer. Available at: https://kings-printer. alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=A25P5.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779744060. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Traffic Safety Act. Alberta Kings’s Printer. Available at: https://kings-printer.alberta. ca/570.cfm?frm_isbn=9780779838714&search_by=link. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2023). Driver Fitness Monitoring. Available at: https://www.alberta.ca/driver-fitness-monitoring.aspx. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- A Practical Guide to Elder Abuse and Neglect Law in Canada https://www.bcli.org/sites/default/files/Practical_ Guide_English_Rev_JULY_2011.pdf

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Protection for Persons In Care Act. Available at: https://kings-printer.alberta. ca/1266.cfm?page=P29P1.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbnc ln=9780779839711. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act. Alberta King’s Printer. Available at: https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=C12. cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779839162. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Personal Information Protection Act. Alberta King’s Printer. Available at: https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=P06P5.cfm&leg_ type=Acts&isbncln=9780779839650. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Health Information Act. Alberta King’s Printer. Available at: https://kings-printer. alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=P06P5.cfm&leg_type=Acts&is bncln=9780779839650. Accessed on April 4, 2023.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). Workers’ Compensation Act. Alberta King’s Printer. Available at: https://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/W15.pdf. Accessed on April 4, 2023.